Developing Plugins ¶¶

This page describes how to write your own FiftyOne plugins.

Note

Check out the FiftyOne plugins repository for a growing collection of plugins that you can use as examples when developing your own.

Design overview ¶¶

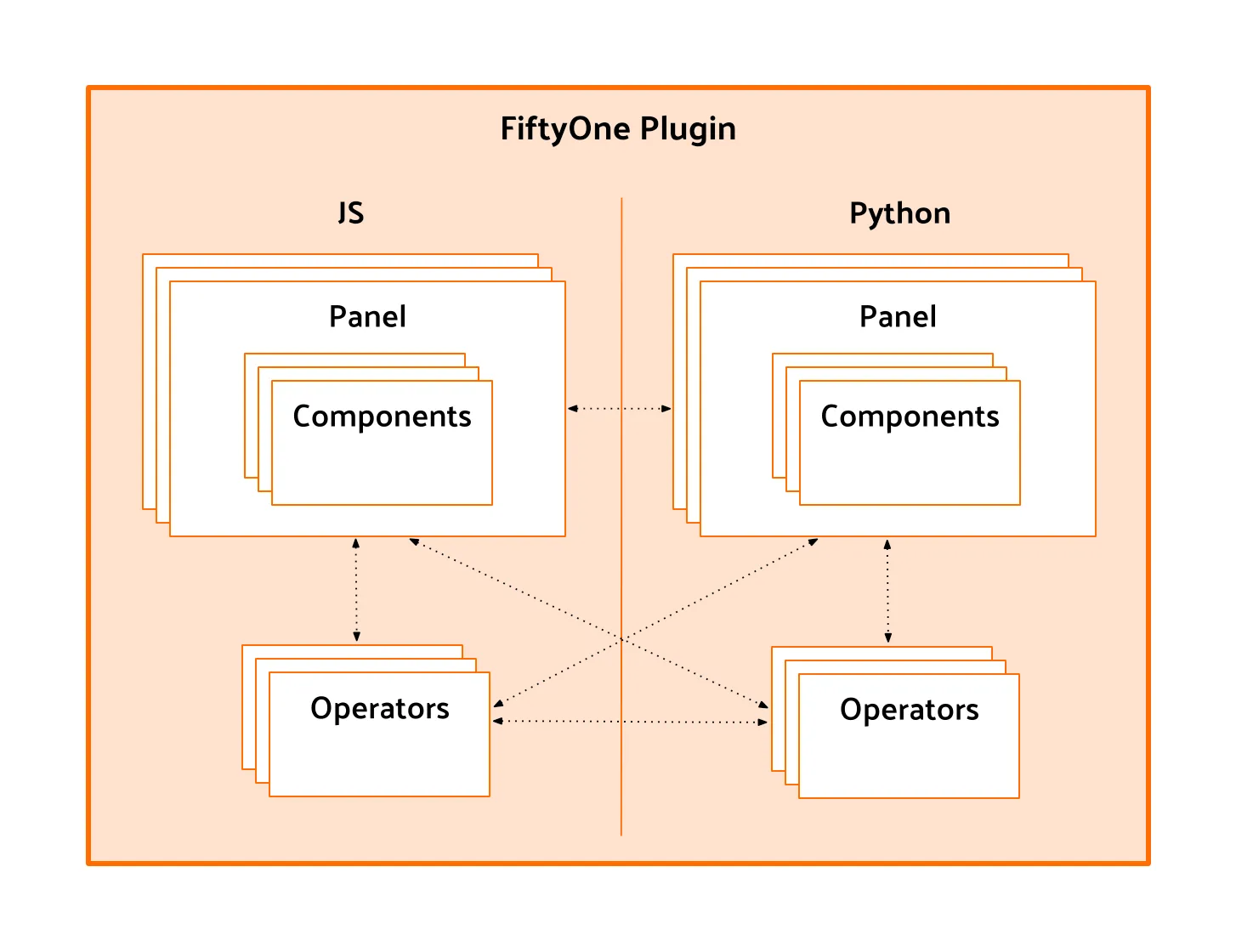

Plugins are composed of one or more panels, operators, and components.

Together these building blocks enable you to build full-featured interactive data applications that tailor FiftyOne to your specific use case and workflow. Whether you’re working with images, videos, or other data types, a plugin can help you streamline your machine learning workflows and co-develop your data and models.

Plugin types ¶¶

FiftyOne plugins can be written in Python or JavaScript (JS), or a combination of both.

Python plugins are built using the fiftyone package, pip packages, and your

own Python. They can consist of panels and operators.

JS plugins are built using the @fiftyone TypeScript packages, npm packages,

and your own TypeScript. They can consist of panels, operators, and custom

components.

Panels ¶¶

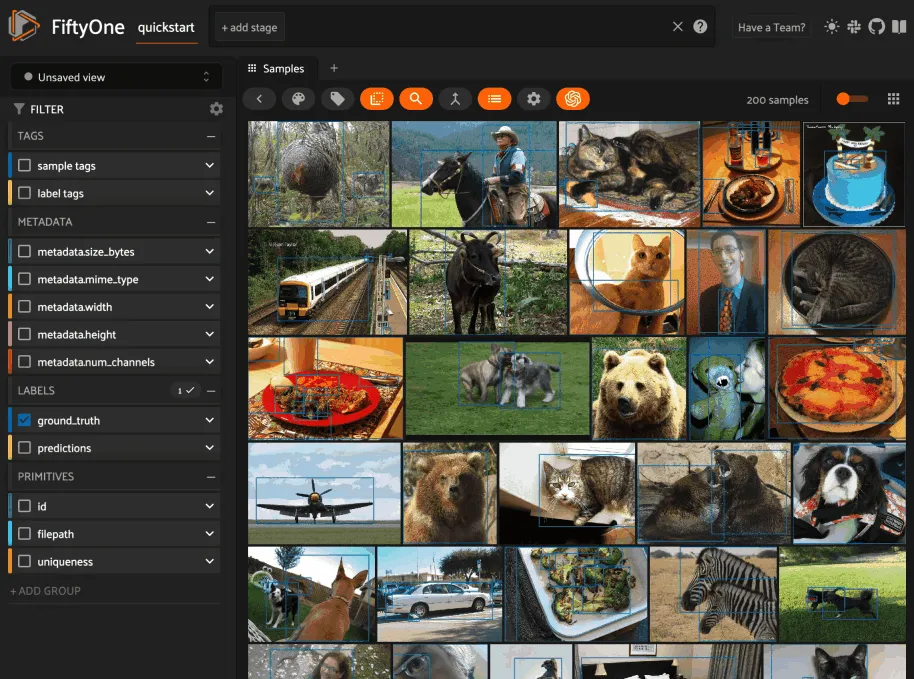

Panels are miniature full-featured data applications that you can open in App spaces and interactively manipulate to explore your dataset and update/respond to updates from other spaces that are currently open in the App.

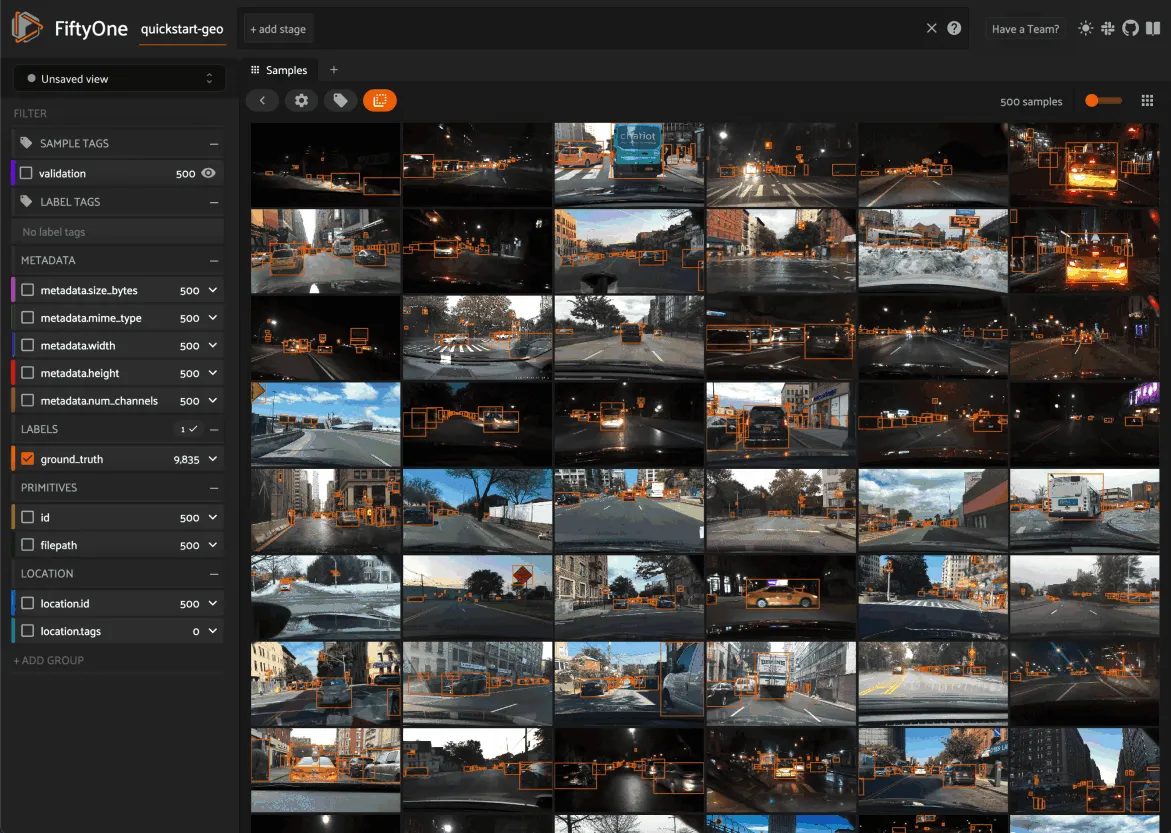

FiftyOne natively includes the following Panels:

-

Samples panel: the media grid that loads by default when you launch the App

-

Histograms panel: a dashboard of histograms for the fields of your dataset

-

Embeddings panel: a canvas for working with embeddings visualizations

-

Map panel: visualizes the geolocation data of datasets that have a

GeoLocationfield

Note

Jump to this section for more information about developing panels.

Operators ¶¶

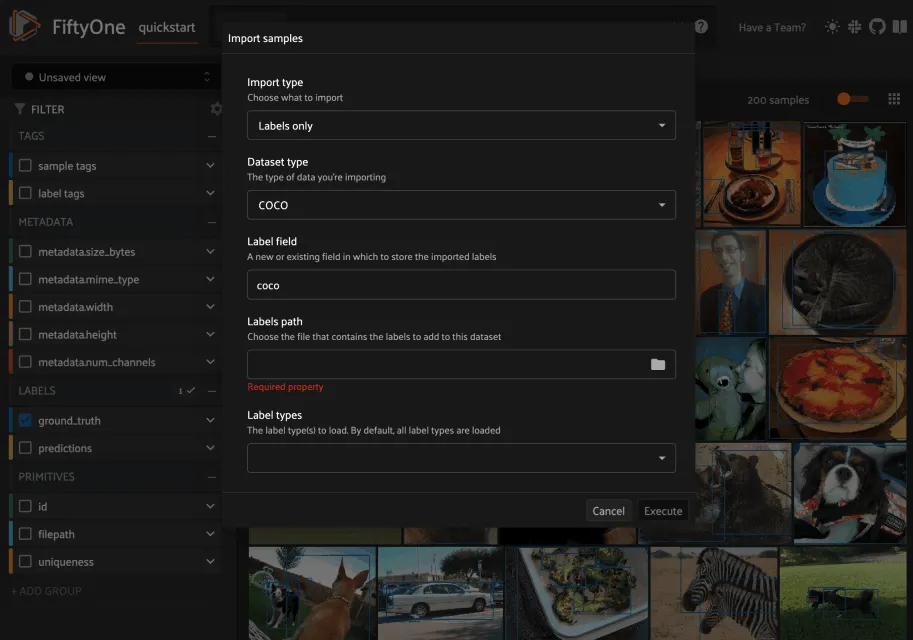

Operators are user-facing operations that allow you to interact with the data in your dataset. They can range from simple actions like checking a checkbox to more complex workflows such as requesting annotation of samples from a configurable backend. Operators can even be composed of other operators or be used to add functionality to custom panels.

FiftyOne comes with a number of builtin

Python and

JavaScript

operators for common tasks that are intended for either user-facing or internal

plugin use.

Note

Jump to this section for more information about developing operators.

Components ¶¶

Components are responsible for rendering and event handling in plugins. They provide the necessary functionality to display and interact with your plugin in the FiftyOne App. Components also implement form inputs and output rendering for operators, making it possible to customize the way an operator is rendered in the FiftyOne App.

For example, FiftyOne comes with a wide variety of

builtin types that you can leverage to build

complex input and output forms for your operators.

Note

Jump to this section for more information about developing components.

Development setup ¶¶

In order to develop Python plugins, you can use either a release or source install of FiftyOne:

pip install fiftyone

In order to develop JS plugins, you will need a

source install

of FiftyOne and a vite config that links modules to your fiftyone/app

directory.

Note

For JS plugins we recommend forking the FiftyOne Hello World JS Example repository and following the conventions there to build your JS plugin.

Anatomy of a plugin ¶¶

FiftyOne recognizes plugins by searching for fiftyone.yml or fiftyone.yaml

files within your plugins directory.

Below is an example of a plugin directory with a typical Python plugin and JS plugin:

/path/to/your/plugins/dir/

my-js-plugin/

fiftyone.yml

package.json

dist/

index.umd.js

my-py-plugin/

fiftyone.yml

__init__.py

requirements.txt

Note

If the source code for a plugin already exists on disk, you can make it

into a plugin using

create_plugin() or the

fiftyone plugins create CLI command.

This will copy the source code to the plugins directory and create a

fiftyone.yml file for you if one does not already exist. Alternatively,

you can manually copy the code into your plugins directory.

If your FiftyOne App is already running, you may need to restart the server and refresh your browser to see new plugins.

fiftyone.yml ¶¶

All plugins must contain a fiftyone.yml or fiftyone.yaml file, which is

used to define the plugin’s metadata, declare any operators and panels that it

exposes, and declare any secrets that it may require.

The following fields are available:

| Field | Required? | Description |

|---|---|---|

name |

yes | The name of the plugin |

type |

Declare that the directory defines a plugin. This can be omitted forbackwards compatibility, but it is recommended to specify this |

|

author |

The author of the plugin | |

version |

The version of the plugin | |

url |

The remote source (eg GitHub repository) where the directory containing this file is hosted |

|

license |

The license under which the plugin is distributed | |

description |

A brief description of the plugin | |

fiftyone.version |

A semver version specifier (or *) describing the requiredFiftyOne version for the plugin to work properly |

|

operators |

A list of operator names registered by the plugin, if any | |

panels |

A list of panel names registered by the plugin, if any | |

secrets |

A list of secret keys that may be used by the plugin, if any |

For example, the

@voxel51/annotation

plugin’s fiftyone.yml looks like this:

name: "@voxel51/annotation"

type: plugin

author: Voxel51

version: 1.0.0

url: https://github.com/voxel51/fiftyone-plugins/tree/main/plugins/annotation

license: Apache 2.0

description: Utilities for integrating FiftyOne with annotation tools

fiftyone:

version: ">=0.22"

operators:

- request_annotations

- load_annotations

- get_annotation_info

- load_annotation_view

- rename_annotation_run

- delete_annotation_run

secrets:

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_URL

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_USERNAME

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_PASSWORD

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_EMAIL

- FIFTYONE_LABELBOX_URL

- FIFTYONE_LABELBOX_API_KEY

- FIFTYONE_LABELSTUDIO_URL

- FIFTYONE_LABELSTUDIO_API_KEY

Note

Although it is not strictly required, we highly recommend using the

@user-or-org-name/plugin-name naming convention when writing plugins.

Python plugins ¶¶

Python plugins should define the following files:

-

__init__.py(required): entrypoint that defines the Python operators and panels that the plugin defines -

requirements.txt: specifies the Python package requirements to run the plugin

JS plugins ¶¶

JS plugins should define the following files:

-

package.json: a JSON file containing additional information about the plugin, including the JS bundle file path -

dist/index.umd.js: a JS bundle file for the plugin

Publishing plugins ¶¶

You can publish your FiftyOne plugins either privately or publicly by simply uploading the source directory or a ZIP of it to GitHub or another file hosting service.

Note

Want to share your plugin with the FiftyOne community? Make a pull request into the FiftyOne Plugins repository to add it to the Community Plugins list!

Any users with access to the plugin’s hosted location can easily download it via the fiftyone plugins download CLI command:

# Download plugin(s) from a GitHub repository

fiftyone plugins download https://github.com/<user>/<repo>[/tree/branch]

# Download plugin(s) by specifying the GitHub repository details

fiftyone plugins download <user>/<repo>[/<ref>]

# Download specific plugins from a GitHub repository

fiftyone plugins download \\

https://github.com/<user>/<repo>[/tree/branch] \\

--plugin-names <name1> <name2> <name3>

Note

GitHub repositories may contain multiple plugins. By default, all plugins that are found within the first three directory levels are installed, but you can select specific ones if desired as shown above.

Quick examples ¶¶

This section contains a few quick examples of plugins before we dive into the full details of the plugin system.

Note

The best way to learn how to write plugins is to use and inspect existing ones. Check out the FiftyOne plugins repository for a growing collection of plugins that you can use as examples when developing your own.

Example plugin ¶¶

The Hello World plugin defines both a JS Panel and a Python operator:

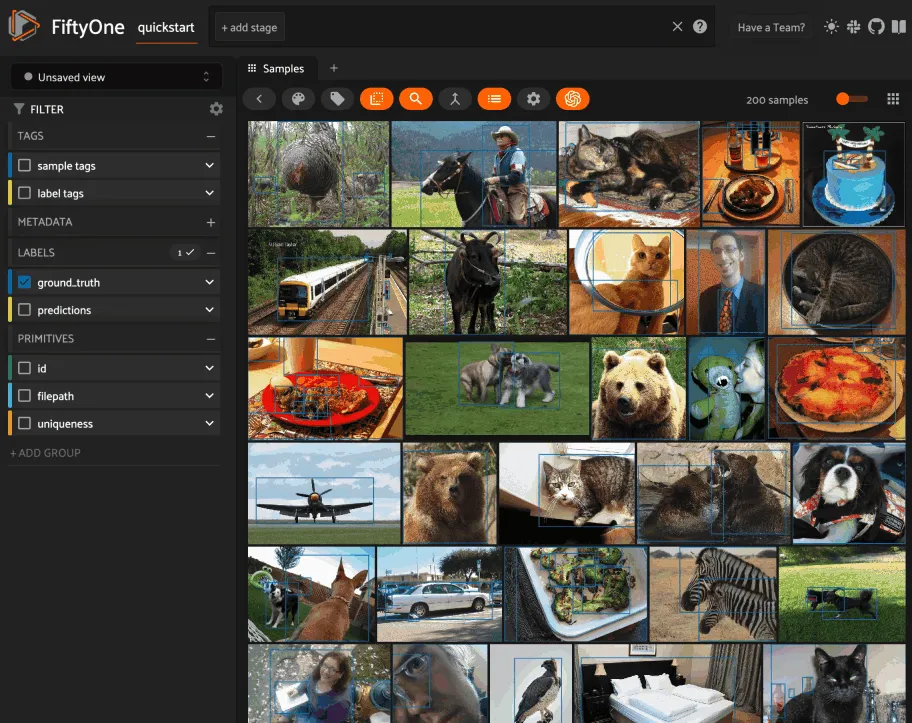

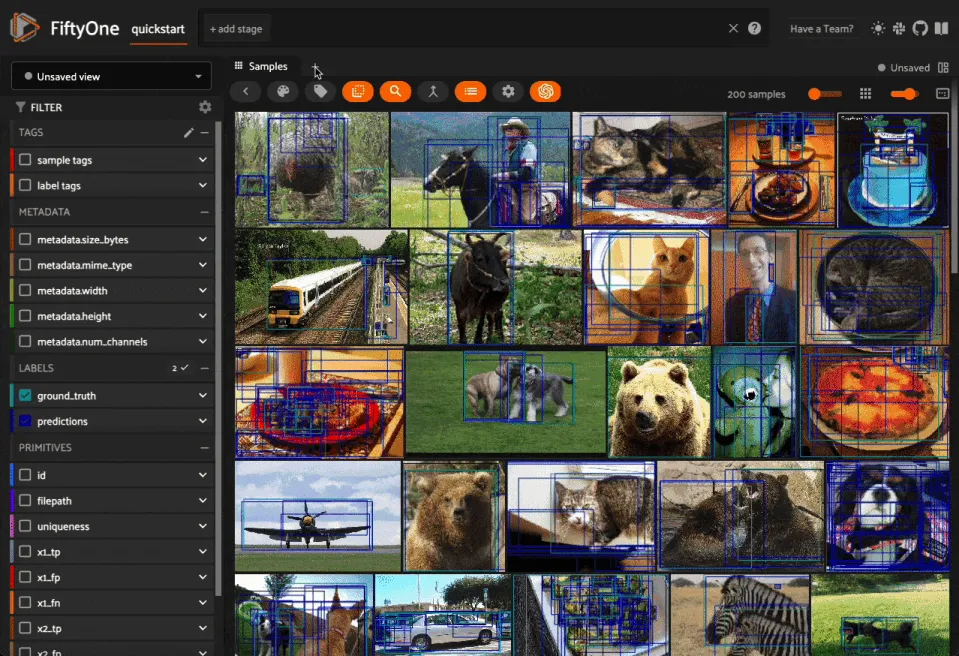

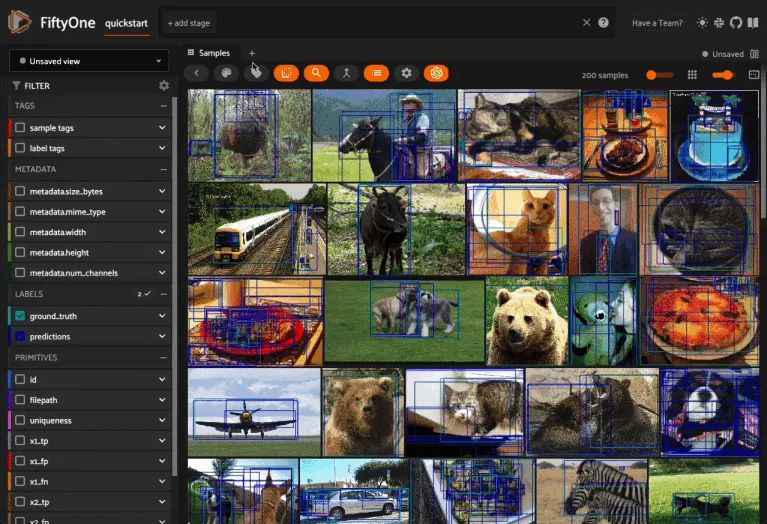

Here’s the plugin in action! The Hello world panel is available under the +

icon next to the Samples tab and the count_samples operator is available in

the operator browser:

Example Python operator ¶¶

Here’s a simple Python operator that accepts a string input and then displays it to the user in the operator’s output modal.

class SimpleInputExample(foo.Operator):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.OperatorConfig(

name="simple_input_example",

label="Simple input example",

)

def resolve_input(self, ctx):

inputs = types.Object()

inputs.str("message", label="Message", required=True)

header = "Simple input example"

return types.Property(inputs, view=types.View(label=header))

def execute(self, ctx):

return {"message": ctx.params["message"]}

def resolve_output(self, ctx):

outputs = types.Object()

outputs.str("message", label="Message")

header = "Simple input example: Success!"

return types.Property(outputs, view=types.View(label=header))

def register(p):

p.register(SimpleInputExample)

In practice, operators would use the inputs to perform some operation on the current dataset.

Note

Remember that you must also include the operator’s name in the plugin’s fiftyone.yml:

operators:

- simple_input_example

Example Python panel ¶¶

Here’s a simple Python panel that renders a button that shows a “Hello world!” notification when clicked:

import fiftyone.operators as foo

import fiftyone.operators.types as types

class HelloWorldPanel(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

name="hello_world_panel",

label="Hello World Panel"

)

def on_load(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.hello_message = "Hello world!"

def say_hello(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.notify(ctx.panel.state.hello_message)

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

panel.btn(

"hello_btn",

label="Say Hello",

icon="emoji_people",

on_click=self.say_hello,

variant="contained",

)

panel_view = types.GridView(

width=100, height=100, align_x="center", align_y="center"

)

return types.Property(panel, view=panel_view)

def register(p):

p.register(HelloWorldPanel)

Note

Remember that you must also include the panel’s name in the plugin’s fiftyone.yml:

panels:

- hello_world_panel

Example JS operator ¶¶

Here’s how to define a JS operator that sets the

currently selected samples in the App based on a list of sample IDs provided

via a samples parameter.

import {Operator, OperatorConfig, types, registerOperator} from "@fiftyone/operators";

const PLUGIN_NAME = "@my/plugin";

class SetSelectedSamples extends Operator {

get config(): OperatorConfig {

return new OperatorConfig({

name: "set_selected_samples",

label: "Set selected samples",

unlisted: true,

});

}

useHooks(): {} {

return {

setSelected: fos.useSetSelected(),

};

}

async execute({ hooks, params }: ExecutionContext) {

hooks.setSelected(params.samples);

}

}

registerOperator(SetSelectedSamples, PLUGIN_NAME);

Unlike Python operators, JS operators can use React hooks and the @fiftyone/*

packages by defining a useHook() method. Any values return in this method

will be available to the operator’s execute() method via ctx.hooks.

Note

Marking the operator as unlisted omits it from the

operator browser, which is useful when the

operator is intended only for internal use by other plugin components.

Developing operators ¶¶

Operators allow you to define custom operations that accept parameters via input properties, execute some actions based on them, and optionally return outputs. They can be executed by users in the App or triggered internally by other operators.

Operators can be defined in either Python or JS, and FiftyOne comes with a

number of builtin Python and

JS

operators for common tasks.

The fiftyone.operators.types module and

@fiftyone/operators package define a rich

builtin type system that operator developers can use to define the input and

output properties of their operators without the need to build custom user

interfaces from scratch. These types handle all aspects of input collection,

validation, and component rendering for you.

Operators can be composed for coordination between Python and the FiftyOne App, such as triggering a reload of samples/view to update the app with the changes made by the operator. Operators can also be scheduled to run by an orchestrator or triggered by other operators.

Operator interface ¶¶

The code block below describes the Python interface for defining operators. We’ll dive into each component of the interface in more detail in the subsequent sections.

Note

The JS interface for defining operators is analogous. See this example JS operator for details.

import fiftyone.operators as foo

import fiftyone.operators.types as types

class ExampleOperator(foo.Operator):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.OperatorConfig(

# The operator's URI: f"{plugin_name}/{name}"

name="example_operator", # required

# The display name of the operator

label="Example operator", # required

# A description for the operator

description="An example description"

# Whether to re-execute resolve_input() after each user input

dynamic=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator's execute() method returns a generator

# that should be iterated over until exhausted

execute_as_generator=True/False, # default False

# Whether to hide this operator from the App's operator browser

# Set this to True if the operator is only for internal use

unlisted=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator should be executed every time a new App

# session starts

on_startup=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator should be executed every time a new

# dataset is opened in the App

on_dataset_open=True/False, # default False

# Custom icons to use

# Can be a URL, a local path in the plugin directory, or the

# name of a MUI icon: https://marella.me/material-icons/demo

icon="/assets/icon.svg",

light_icon="/assets/icon-light.svg", # light theme only

dark_icon="/assets/icon-dark.svg", # dark theme only

# Whether the operator supports immediate and/or delegated execution

allow_immediate_execution=True/False, # default True

allow_delegated_execution=True/False, # default False

default_choice_to_delegated=True/False, # default False

resolve_execution_options_on_change=None,

)

def resolve_placement(self, ctx):

"""You can optionally implement this method to configure a button

or icon in the App that triggers this operator.

By default the operator only appears in the operator browser

(unless it is unlisted).

Returns:

a `types.Placement`

"""

return types.Placement(

# Make operator appear in the actions row above the sample grid

types.Places.SAMPLES_GRID_SECONDARY_ACTIONS,

# Use a button as the operator's placement

types.Button(

# A label for placement button visible on hover

label="Open Histograms Panel",

# An icon for the button

# The default is a button with the `label` displayed

icon="/assets/icon.svg",

# If False, don't show the operator's input prompt when we

# do not require user input

prompt=True/False # False

)

)

def resolve_input(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to collect user inputs as parameters

that are stored in `ctx.params`.

Returns:

a `types.Property` defining the form's components

"""

inputs = types.Object()

# Use the builtin `types` and the current `ctx.params` to define

# the necessary user input data

inputs.str("key", ...)

# When `dynamic=True`, you'll often use the current `ctx` to

# conditionally render different components

if ctx.params["key"] == "value" and len(ctx.view) < 100:

# do something

else:

# do something else

return types.Property(inputs, view=types.View(label="Example operator"))

def resolve_delegation(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method if you want to programmatically *force*

this operation to be delegated or executed immediately.

Returns:

whether the operation should be delegated (True), run

immediately (False), or None to defer to

`resolve_execution_options()` to specify the available options

"""

return len(ctx.view) > 1000 # delegate for larger views

def resolve_execution_options(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method if you want to dynamically configure the

execution options available to this operator based on the current

`ctx`.

Returns:

an `ExecutionOptions` instance

"""

should_delegate = len(ctx.view) > 1000 # delegate for larger views

return foo.ExecutionOptions(

allow_immediate_execution=True,

allow_delegated_execution=True,

default_choice_to_delegated=should_delegate,

)

def execute(self, ctx):

"""Executes the actual operation based on the hydrated `ctx`.

All operators must implement this method.

This method can optionally be implemented as `async`.

Returns:

an optional dict of results values

"""

# Use ctx.params, ctx.dataset, ctx.view, etc to perform the

# necessary computation

value = ctx.params["key"]

view = ctx.view

n = len(view)

# Use ctx.ops to trigger builtin operations

ctx.ops.clear_selected_samples()

ctx.ops.set_view(view=view)

# Use ctx.trigger to call other operators as necessary

ctx.trigger("operator_uri", params={"key": value})

# If `execute_as_generator=True`, this method may yield multiple

# messages

for i, sample in enumerate(current_view, 1):

# do some computation

yield ctx.ops.set_progress(progress=i/n)

yield ctx.ops.reload_dataset()

return {"value": value, ...}

def resolve_output(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method if your operator renders an output form

to the user.

Returns:

a `types.Property` defining the components of the output form

"""

outputs = types.Object()

# Use the builtin `types` and the current `ctx.params` and

# `ctx.results` as necessary to define the necessary output form

outputs.define_property("value", ...)

return types.Property(outputs, view=types.View(label="Example operator"))

def register(p):

"""Always implement this method and register() each operator that your

plugin defines.

"""

p.register(ExampleOperator)

Note

Remember that you must also include the operator’s name in the plugin’s fiftyone.yml:

operators:

- example_operator

Operator config ¶¶

Every operator must define a

config property that

defines its name, display name, and other optional metadata about its

execution:

@property

def config(self):

return foo.OperatorConfig(

# The operator's URI: f"{plugin_name}/{name}"

name="example_operator", # required

# The display name of the operator

label="Example operator", # required

# A description for the operator

description="An example description"

# Whether to re-execute resolve_input() after each user input

dynamic=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator's execute() method returns a generator

# that should be iterated over until exhausted

execute_as_generator=True/False, # default False

# Whether to hide this operator from the App's operator browser

# Set this to True if the operator is only for internal use

unlisted=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator should be executed every time a new App

# session starts

on_startup=True/False, # default False

# Whether the operator should be executed every time a new dataset

# is opened in the App

on_dataset_open=True/False, # default False

# Custom icons to use

# Can be a URL, a local path in the plugin directory, or the

# name of a MUI icon: https://marella.me/material-icons/demo

icon="/assets/icon.svg",

light_icon="/assets/icon-light.svg", # light theme only

dark_icon="/assets/icon-dark.svg", # dark theme only

# Whether the operator supports immediate and/or delegated execution

allow_immediate_execution=True/False, # default True

allow_delegated_execution=True/False, # default False

default_choice_to_delegated=True/False, # default False

resolve_execution_options_on_change=None,

)

Execution context ¶¶

An ExecutionContext is

passed to each of the operator’s methods at runtime. This ctx contains static

information about the current state of the App (dataset, view, panel,

selection, etc) as well as dynamic information about the current parameters and

results.

An ExecutionContext

contains the following properties:

-

ctx.params: a dict containing the operator’s current input parameter values -

ctx.dataset_name: the name of the current dataset -

ctx.dataset- the currentDatasetinstance -

ctx.view- the currentDatasetViewinstance -

ctx.spaces- the current Spaces layout in the App -

ctx.current_sample- the ID of the active sample in the App modal, if any -

ctx.selected- the list of currently selected samples in the App, if any -

ctx.selected_labels- the list of currently selected labels in the App, if any -

ctx.extended_selection- the extended selection of the view, if any -

ctx.group_slice- the active group slice in the App, if any -

ctx.user_id- the ID of the user that invoked the operator, if known -

ctx.user- an object of information about the user that invoked the operator, if known, including the user’sid,name,email,role, anddataset_permission -

ctx.user_request_token- the request token authenticating the user executing the operation, if known -

ctx.panel_id- the ID of the panel that invoked the operator, if any -

ctx.panel- aPanelRefinstance that you can use to read and write the state and data of the current panel, if the operator was invoked from a panel -

ctx.delegated- whether the operation was delegated -

ctx.requesting_delegated_execution- whether delegated execution was requested for the operation -

ctx.delegation_target- the orchestrator to which the operation should be delegated, if applicable -

ctx.ops- anOperationsinstance that you can use to trigger builtin operations on the current context -

ctx.trigger- a method that you can use to trigger arbitrary operations on the current context -

ctx.secrets- a dict of secrets for the plugin, if any -

ctx.results- a dict containing the outputs of theexecute()method, if it has been called -

ctx.hooks(JS only) - the return value of the operator’suseHooks()method

Operator inputs ¶¶

Operators can optionally implement

resolve_input()

to define user input forms that are presented to the user as a modal in the App

when the operator is invoked.

The basic objective of

resolve_input()

is to populate the ctx.params dict with user-provided parameter values, which

are retrieved from the various subproperties of the

Property returned by the method

( inputs in the examples below).

The fiftyone.operators.types module defines a rich builtin type system

that you can use to define the necessary input properties. These types handle

all aspects of input collection, validation, and component rendering for you!

For example, here’s a simple example of collecting a single string input from the user:

def resolve_input(self, ctx):

inputs = types.Object()

inputs.str("message", label="Message", required=True)

return types.Property(inputs, view=types.View(label="Static example"))

def execute(self, ctx):

the_message = ctx.params["message"]

If the operator’s config declares dynamic=True, then

resolve_input()

will be called after each user input, which allows you to construct dynamic

forms whose components may contextually change based on the already provided

values and any other aspects of the

execution context:

import fiftyone.brain as fob

def resolve_input(self, ctx):

inputs = types.Object()

brain_keys = ctx.dataset.list_brain_runs()

if not brain_keys:

warning = types.Warning(label="This dataset has no brain runs")

prop = inputs.view("warning", warning)

prop.invalid = True # so form's `Execute` button is disabled

return

choices = types.DropdownView()

for brain_key in brain_keys:

choices.add_choice(brain_key, label=brain_key)

inputs.str(

"brain_key",

required=True,

label="Brain key",

description="Choose a brain key to use",

view=choices,

)

brain_key = ctx.params.get("brain_key", None)

if brain_key is None:

return # single `brain_key`

info = ctx.dataset.get_brain_info(brain_key)

if isinstance(info.config, fob.SimilarityConfig):

# We found a similarity config; render some inputs specific to that

inputs.bool(

"upgrade",

label"Compute visualization",

description="Generate an embeddings visualization for this index?",

view=types.CheckboxView(),

)

return types.Property(inputs, view=types.View(label="Dynamic example"))

Remember that properties automatically handle validation for you. So if you

configure a property as required=True but the user has not provided a value,

the property will automatically be marked as invalid=True. The operator’s

Execute button will be enabled if and only if all input properties are valid

(recursively searching nested objects).

Note

As the example above shows, you can manually set a property to invalid by

setting its invalid property.

Note

Avoid expensive computations in

resolve_input()

or else the form may take too long to render, especially for dynamic inputs

where the method is called after every user input.

Delegated execution ¶¶

By default, operations are executed immediately after their inputs are provided in the App or they are triggered programmatically.

However, many interesting operations like model inference, embeddings computation, evaluation, and exports are computationally intensive and/or not suitable for immediate execution.

In such cases, delegated operations come to the rescue by allowing users to schedule potentially long-running tasks that are executed in the background while you continue to use the App.

Note

FiftyOne Teams deployments come out of the box with a connected compute cluster for executing delegated operations at scale.

In FiftyOne Open Source, you can use delegated operations at small scale by running them locally.

There are a variety of options available for configuring whether a given operation should be delegated or executed immediately.

Execution options ¶¶

You can provide the optional properties described below in the operator’s config to specify the available execution modes for the operator:

@property

def config(self):

return foo.OperatorConfig(

# Other parameters...

# Whether to allow immediate execution

allow_immediate_execution=True/False, # default True

# Whether to allow delegated execution

allow_delegated_execution=True/False, # default False

# Whether the default execution mode should be delegated, if both

# options are available

default_choice_to_delegated=True/False, # default False

# Whether to resolve execution options dynamically when the

# operator's inputs change. By default, this behavior will match

# the operator's ``dynamic`` setting

resolve_execution_options_on_change=True/False/None, # default None

)

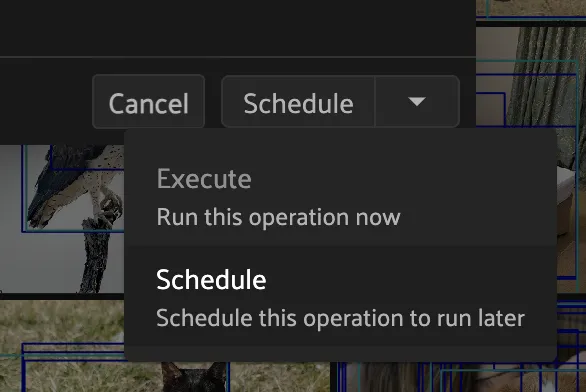

When the operator’s input form is rendered in the App, the Execute|Schedule

button at the bottom of the modal will contextually show whether the operation

will be executed immediately, scheduled for delegated execution, or allow the

user to choose between the supported options if there are multiple:

Dynamic execution options ¶¶

Operators may also implement

resolve_execution_options()

to dynamically configure the available execution options based on the current

execution context:

# Option 1: recommend delegation for larger views

def resolve_execution_options(self, ctx):

should_delegate = len(ctx.view) > 1000

return foo.ExecutionOptions(

allow_immediate_execution=True,

allow_delegated_execution=True,

default_choice_to_delegated=should_delegate,

)

# Option 2: force delegation for larger views

def resolve_execution_options(self, ctx):

delegate = len(ctx.view) > 1000

return foo.ExecutionOptions(

allow_immediate_execution=not delegate,

allow_delegated_execution=delegate,

)

If implemented, this method will override any static execution parameters included in the operator’s config as described in the previous section.

Forced delegation ¶¶

Operators can implement

resolve_delegation()

to force a particular operation to be delegated (by returning True) or

executed immediately (by returning False) based on the current execution

context.

For example, you could decide whether to delegate execution based on the size of the current view:

def resolve_delegation(self, ctx):

# Force delegation for large views and immediate execution for small views

return len(ctx.view) > 1000

If resolve_delegation()

is not implemented or returns None, then the choice of execution mode is

deferred to the prior mechanisms described above.

Reporting progress ¶¶

Delegated operations can report their execution progress by calling

set_progress()

on their execution context from within

execute():

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.core.storage as fos

import fiftyone.core.utils as fou

def execute(self, ctx):

images_dir = ctx.params["images_dir"]

filepaths = fos.list_files(images_dir, abs_paths=True, recursive=True)

num_added = 0

num_total = len(filepaths)

for batch in fou.iter_batches(filepaths, 100):

samples = [fo.Sample(filepath=f) for f in batch]

ctx.dataset.add_samples(samples)

num_added += len(batch)

ctx.set_progress(progress=num_added / num_total)

Note

FiftyOne Teams users can view the current progress of their delegated operations from the Runs page of the Teams App!

For your convenience, all builtin methods of the FiftyOne SDK that support

rendering progress bars provide an optional progress method that you can use

trigger calls to

set_progress()

using the pattern show below:

import fiftyone as fo

def execute(self, ctx):

images_dir = ctx.params["images_dir"]

# Custom logic that controls how progress is reported

def set_progress(pb):

if pb.complete:

ctx.set_progress(progress=1, label="Operation complete")

else:

ctx.set_progress(progress=pb.progress)

# Option 1: report progress every five seconds

progress = fo.report_progress(set_progress, dt=5.0)

# Option 2: report progress at 10 equally-spaced increments

# progress = fo.report_progress(set_progress, n=10)

ctx.dataset.add_images_dir(images_dir, progress=progress)

You can also use the builtin

ProgressHandler class to

automatically forward logging messages to

set_progress()

as label values using the pattern shown below:

import logging

import fiftyone.operators as foo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

def execute(self, ctx):

name = ctx.params["name"]

# Automatically report all `fiftyone` logging messages

with foo.ProgressHandler(ctx, logger=logging.getLogger("fiftyone")):

foz.load_zoo_dataset(name, persistent=True)

Operator execution ¶¶

All operators must implement

execute(), which is

where their main actions are performed.

The execute() method

takes an execution context as input whose

ctx.params dict has been hydrated with parameters provided either by the

user by filling out the operator’s input form or

directly provided by the operation that triggered it. The method can optionally

return a dict of results values that will be made available via ctx.results

when the operator’s output form is rendered.

Synchronous execution ¶¶

Your execution method is free to make use of the full power of the FiftyOne SDK and any external dependencies that it needs.

For example, you might perform inference on a model:

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

def execute(self, ctx):

name = ctx.params["name"]

label_field = ctx.params["label_field"]

confidence_thresh = ctx.params.get("confidence_thresh", None)

model = foz.load_zoo_model(name)

ctx.view.apply_model(

model, label_field=label_field, confidence_thresh=confidence_thresh

)

num_predictions = ctx.view.count(f"{label_field}.detections")

return {"num_predictions": num_predictions}

Note

When an operator’s

execute() method

throws an error it will be displayed to the user in the browser.

Asynchronous execution ¶¶

The execute() method

can also be async:

import aiohttp

async def execute(self, ctx):

# do something async

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

async with session.get(url) as resp:

r = await resp.json()

Operator composition ¶¶

Many operators are designed to be composed with other operators to build up

more complex behaviors. You can trigger other operations from within an

operator’s execute()

method via ctx.ops and

ctx.trigger.

The ctx.ops property of an

execution context exposes all builtin

Python and

JavaScript

in a conveniently documented functional interface. For example, many operations

involve updating the current state of the App:

def execute(self, ctx):

# Dataset

ctx.ops.open_dataset("...")

ctx.ops.reload_dataset()

# View/sidebar

ctx.ops.set_view(name="...") # saved view by name

ctx.ops.set_view(view=view) # arbitrary view

ctx.ops.clear_view()

ctx.ops.clear_sidebar_filters()

# Selected samples

ctx.ops.set_selected_samples([...]))

ctx.ops.clear_selected_samples()

# Selected labels

ctx.ops.set_selected_labels([...])

ctx.ops.clear_selected_labels()

# Panels

ctx.ops.open_panel("Embeddings")

ctx.ops.close_panel("Embeddings")

The ctx.trigger

property is a lower-level function that allows you to invoke arbitrary

operations by providing their URI and parameters, including all builtin

operations as well as any operations installed via custom plugins. For example,

here’s how to trigger the same App-related operations from above:

def execute(self, ctx):

# Dataset

ctx.trigger("open_dataset", params=dict(name="..."))

ctx.trigger("reload_dataset") # refreshes the App

# View/sidebar

ctx.trigger("set_view", params=dict(name="...")) # saved view by name

ctx.trigger("set_view", params=dict(view=view._serialize())) # arbitrary view

ctx.trigger("clear_view")

ctx.trigger("clear_sidebar_filters")

# Selected samples

ctx.trigger("set_selected_samples", params=dict(samples=[...]))

ctx.trigger("clear_selected_samples")

# Selected labels

ctx.trigger("set_selected_labels", params=dict(labels=[...]))

ctx.trigger("clear_selected_labels")

# Panels

ctx.trigger("open_panel", params=dict(name="Embeddings"))

ctx.trigger("close_panel", params=dict(name="Embeddings"))

Generator execution ¶¶

If your operator’s config declares that it is a

generator via execute_as_generator=True, then its

execute() method should

yield calls to

ctx.ops methods or

ctx.trigger(),

both of which trigger another operation and return a

GeneratedMessage

instance containing the result of the invocation.

For example, a common generator pattern is to use the builtin set_progress

operator to render a progress bar tracking the progress of an operation:

def execute(self, ctx):

# render a progress bar tracking the execution

for i in range(n):

# [process a chunk here]

# Option 1: ctx.ops

yield ctx.ops.set_progress(progress=i/n, label=f"Processed {i}/{n}")

# Option 2: ctx.trigger

yield ctx.trigger(

"set_progress",

dict(progress=i/n, label=f"Processed {i}/{n}"),

)

Note

Check out the VoxelGPT plugin for a more sophisticated example of using generator execution to stream an LLM’s response to a panel.

Accessing secrets ¶¶

Some plugins may require sensitive information such as API tokens and login credentials in order to function. Any secrets that a plugin requires are in its fiftyone.yml.

For example, the @voxel51/annotation plugin declares the following secrets:

secrets:

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_URL

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_USERNAME

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_PASSWORD

- FIFTYONE_CVAT_EMAIL

- FIFTYONE_LABELBOX_URL

- FIFTYONE_LABELBOX_API_KEY

- FIFTYONE_LABELSTUDIO_URL

- FIFTYONE_LABELSTUDIO_API_KEY

As the naming convention implies, any necessary secrets are provided by users by setting environment variables with the appropriate names. For example, if you want to use the CVAT backend with the @voxel51/annotation plugin, you would set:

FIFTYONE_CVAT_URL=...

FIFTYONE_CVAT_USERNAME=...

FIFTYONE_CVAT_PASSWORD=...

FIFTYONE_CVAT_EMAIL=...

At runtime, the plugin’s execution context

is automatically hydrated with any available secrets that are declared by the

plugin. Operators can access these secrets via the ctx.secrets dict:

def execute(self, ctx):

url = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_URL"]

username = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_USERNAME"]

password = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_PASSWORD"]

email = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_EMAIL"]

Operator outputs ¶¶

Operators can optionally implement

resolve_output()

to define read-only output forms that are presented to the user as a modal in

the App after the operator’s execution completes.

The basic objective of

resolve_output()

is to define properties that describe how to render the values in ctx.results

for the user. As with input forms, you can use the

fiftyone.operators.types module to define the output properties.

For example, the output form below renders the number of samples ( count)

computed during the operator’s execution:

def execute(self, ctx):

# computation here...

return {"count": count}

def resolve_output(self, ctx):

outputs = types.Object()

outputs.int(

"count",

label="Count",

description=f"The number of samples in the current {target}",

)

return types.Property(outputs)

Note

All properties in output forms are implicitly rendered as read-only.

Operator placement ¶¶

By default, operators are only accessible from the

operator browser. However, you can place a custom

button, icon, menu item, etc. in the App that will trigger the operator when

clicked in any location supported by the

types.Places enum.

For example, you can use:

types.Places.SAMPLES_GRID_ACTIONS

types.Places.SAMPLES_GRID_SECONDARY_ACTIONS

types.Places.SAMPLES_VIEWER_ACTIONS

types.Places.EMBEDDINGS_ACTIONS

types.Places.HISTOGRAM_ACTIONS

types.Places.MAP_ACTIONS

You can add a placement for an operator by implementing the

resolve_placement()

method as demonstrated below:

Developing panels ¶¶

Panels are miniature full-featured data applications that you can open in App spaces and interactively manipulate to explore your dataset and update/respond to updates from other spaces that are currently open in the App.

Panels can be defined in either Python or JS, and FiftyOne comes with a number of builtin panels for common tasks.

Panels can be scoped to the App’s grid view or modal view via their config. Grid panels enable extensibility at the macro level, allowing you to work with entire datasets or views, while modal panels provide extensibility at the micro level, focusing on individual samples and scenarios.

Panels, like operators, can make use of the

fiftyone.operators.types module and the

@fiftyone/operators package, which define a

rich builtin type system that panel developers can use to implement the layout

and associated events that define the panel.

Panels can trigger both Python and JS operators, either programmatically or by interactively launching a prompt that users can fill out to provide the necessary parameters for the operator’s execution. This powerful composability allows panels to define interactive workflows that guide the user through executing workflows on their data and then interactively exploring and analyzing the results of the computation.

Panels can also interact with other components of the App, such as responding to changes in (or programmatically updating) the current dataset, view, current selection, or active sample in the modal.

Panel interface ¶¶

The code block below describes the Python interface for defining panels. We’ll dive into each component of the interface in more detail in the subsequent sections.

Note

See this section for more information on developing panels in JS.

import fiftyone.operators as foo

import fiftyone.operators.types as types

class ExamplePanel(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

# The panel's URI: f"{plugin_name}/{name}"

name="example_panel", # required

# The display name of the panel in the "+" menu

label="Example panel", # required

# Custom icons to use in the "+"" menu

# Can be a URL, a local path in the plugin directory, or the

# name of a MUI icon: https://marella.me/material-icons/demo

icon="/assets/icon.svg",

light_icon="developer_mode", # light theme only

dark_icon="developer_mode", # dark theme only

# Whether to allow multiple instances of the panel to be opened

allow_multiple=False,

# Whether the panel should be available in the grid, modal, or both

# Possible values: "grid", "modal", "grid modal"

surfaces="grid", # default = "grid"

# Markdown-formatted text that describes the panel. This is

# rendered in a tooltip when the help icon in the panel

# title is hovered over

help_markdown="A description of the panel",

)

def render(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to define your panel's layout and events.

This method is called after every panel event is executed (panel

load, button callback, context change event, etc).

Returns:

a `types.Property` defining the panel's components

"""

panel = types.Object()

brain_keys = ctx.panel.get_state("brain_keys", [])

# Define a menu of actions for the panel

menu = panel.menu("menu", variant="square", color="51")

menu.enum(

"brain_key",

label="Choose a brain key", # placeholder text

values=brain_keys,

on_change=self.on_change_brain_key, # custom event callback

)

menu.btn(

"learn_more",

label="Learn more", # tooltip text

icon="help", # material UI icon

on_click=self.on_click_learn_more, # custom event callback

)

# Define components that appear in the panel's main body

panel.str("event", label="The last event", view=types.LabelValueView())

panel.obj(

"event_data", label="The last event data", view=types.JSONView()

)

# Display a checkbox to toggle between plot and compute visualization button

show_compute_visualization_btn = ctx.panel.get_state(

"show_start_button", True

)

panel.bool(

"show_start_button",

label="Show compute visualization button",

on_change=self.on_change_show_start_button,

)

# You can use conditional logic to dynamically change the layout

# based on the current panel state

if show_compute_visualization_btn:

# Define a button with a custom on click event

panel.btn(

"start",

label="Compute visualization", # button text

on_click=self.on_click_start, # custom event callback

variant="contained", # button style

)

else:

# Define an interactive plot with custom callbacks

panel.plot(

"embeddings",

config={}, # plotly config

layout={}, # plotly layout config

on_selected=self.on_selected_embeddings, # custom event callback

height="400px",

)

return types.Property(

panel, view=types.GridView(orientation="vertical")

)

#######################################################################

# Builtin events

#######################################################################

def on_load(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the panel

initially loads.

"""

event = {

"data": None,

"description": "the panel is loaded",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_load")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

# Get the list of brain keys to populate `brain_key` dropdown

visualization_keys = ctx.dataset.list_brain_runs("visualization")

ctx.panel.set_state("brain_keys", visualization_keys)

# Show compute visualization button by default

ctx.panel.set_state("show_start_button", True)

def on_unload(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the panel is

being closed.

"""

event = {

"data": None,

"description": "the panel is unloaded",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_unload")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_ctx(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when any aspect

of the execution context (view, selected samples, filters, etc.) changes.

The current execution context will be available via ``ctx``.

"""

event = {

"data": {

"view": ctx.view._serialize(),

"selected": ctx.selected,

"has_custom_view": ctx.has_custom_view,

},

"description": "the current ExecutionContext",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_ctx")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_dataset(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

dataset is changed.

The new dataset will be available via ``ctx.dataset``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.dataset.name,

"description": "the current dataset name",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_dataset")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_view(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

view is changed.

The new view will be available via ``ctx.view``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.view._serialize(),

"description": "the current view",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_view")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_spaces(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

spaces layout changes.

The current spaces layout will be available via ``ctx.spaces``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.spaces,

"description": "the current spaces layout",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_spaces")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_current_sample(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when a new sample

is loaded in the Sample modal.

The ID of the new sample will be available via

``ctx.current_sample``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.current_sample,

"description": "the current sample",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_current_sample")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_selected(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

selection changes (eg in the Samples panel).

The IDs of the current selected samples will be available via

``ctx.selected``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.selected,

"description": "the current selection",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_selected")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_selected_labels(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

selected labels change (eg in the Sample modal).

Information about the current selected labels will be available

via ``ctx.selected_labels``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.selected_labels,

"description": "the current selected labels",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_selected_labels")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_extended_selection(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

extended selection changes.

The IDs of the current extended selection will be available via

``ctx.extended_selection``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.extended_selection,

"description": "the current extended selection",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_extended_selection")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

def on_change_group_slice(self, ctx):

"""Implement this method to set panel state/data when the current

group slice changes.

The current group slice will be available via ``ctx.group_slice``.

"""

event = {

"data": ctx.group_slice,

"description": "the current group slice",

}

ctx.panel.set_state("event", "on_change_group_slice")

ctx.panel.set_data("event_data", event)

#######################################################################

# Custom events

# These events are defined by user code above and, just like builtin

# events, take `ctx` as input and are followed by a call to render()

#######################################################################

def on_change_brain_key(self, ctx):

# Load expensive content based on current `brain_key`

brain_key = ctx.panel.get_state("menu.brain_key")

results = ctx.dataset.load_brain_results(brain_key)

# Format results for plotly

x, y = zip(*results.points.tolist())

ids = results.sample_ids

plot_data = [\

{"x": x, "y": y, "ids": ids, "type": "scatter", "mode": "markers"}\

]

# Store large content as panel data for efficiency

ctx.panel.set_data("embeddings", plot_data)

# Show plot with embeddings data instead of the compute visualization button

ctx.panel.set_state("show_start_button", False)

def on_click_start(self, ctx):

# Launch an interactive prompt for user to execute an operator

ctx.prompt("@voxel51/brain/compute_visualization")

# Lightweight state update

ctx.panel.set_state("show_start_button", False)

def on_click_learn_more(self, ctx):

# Trigger a builtin operation via `ctx.ops`

url = "https://docs.voxel51.com/plugins/developing_plugins.html"

ctx.ops.notify(f"Check out {url} for more information")

def on_selected_embeddings(self, ctx):

# Get selected points from event params

selected_points = ctx.params.get("data", [])

selected_sample_ids = [d.get("id", None) for d in selected_points]

# Conditionally trigger a builtin operation via `ctx.ops`

if len(selected_sample_ids) > 0:

ctx.ops.set_extended_selection(selected_sample_ids)

def on_change_show_start_button(self, ctx):

# Get current state of the checkbox on change

current_state = ctx.params.get("value", None)

def register(p):

"""Always implement this method and register() each panel that your

plugin defines.

"""

p.register(ExamplePanel)

Note

Remember that you must also include the panel’s name in the plugin’s fiftyone.yml:

panels:

- example_panel

Panel config ¶¶

Every panel must define a

config property that

defines its name, display name, surfaces, and other optional metadata about its

behavior:

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

# The panel's URI: f"{plugin_name}/{name}"

name="example_panel", # required

# The display name of the panel in the "+" menu

label="Example panel", # required

# Custom icons to use in the "+"" menu

# Can be a URL, a local path in the plugin directory, or the

# name of a MUI icon: https://marella.me/material-icons/demo

icon="/assets/icon.svg",

light_icon="/assets/icon-light.svg", # light theme only

dark_icon="/assets/icon-dark.svg", # dark theme only

# Whether to allow multiple instances of the panel to be opened

allow_multiple=False,

# Whether the panel should be available in the grid, modal, or both

# Possible values: "grid", "modal", "grid modal"

surfaces="grid", # default = "grid"

# Markdown-formatted text that describes the panel. This is

# rendered in a tooltip when the help icon in the panel

# title is hovered over

help_markdown="A description of the panel",

)

The surfaces key defines the panel’s scope:

-

Grid panels can be accessed from the

+button in the App’s grid view, which allows you to build macro experiences that work with entire datasets or views -

Modal panels can be accessed from the

+button in the App’s modal view, which allows you to build interactions that focus on individual samples and scenarios

Note

For an example of a modal panel, refer to the label count panel.

Execution context ¶¶

An ExecutionContext is

passed to each of the panel’s methods at runtime. This ctx contains static

information about the current state of the App (dataset, view, panel,

selection, etc) as well as dynamic information about the panel’s current

state and data.

See this section for a full description of the execution context.

Panel state and data ¶¶

Panels provide two mechanisms for persisting information: panel state and panel data.

Basic structure ¶¶

Panel state can be accessed and updated via ctx.panel.state, and panel data

can be updated (but not accessed) via ctx.panel.data.

Under the hood, panel state and data is merged into a single nested object that

maps 1-1 to the structure and naming of the properties defined by the panel’s

render() method.

The example code below shows how to access and update panel state.

Note

Since panel state and panel data are merged into a single object, it is important to avoid naming conflicts between state and data keys. If a key is present in both panel state and data, the value in panel data will be used.

class CounterPanel(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

name="counter_panel", label="Counter Panel", icon="123"

)

def on_load(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.v_stack = {"h_stack": {"count": 3}}

def increment(self, ctx):

count = ctx.panel.state.get("v_stack.h_stack.count", 0)

ctx.panel.state.set("v_stack.h_stack.count", count + 1)

def decrement(self, ctx):

count = ctx.panel.get_state("v_stack.h_stack.count", 0)

ctx.panel.set_state("v_stack.h_stack.count", count - 1)

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

# Define a vertical stack object with the name 'v_stack'

# key: 'v_stack'

v_stack = panel.v_stack("v_stack", align_x="center", gap=2)

# Define a horizontal stack object with the name 'h_stack' on 'v_stack'

# key: 'v_stack.h_stack'

h_stack = v_stack.h_stack("h_stack", align_y="center")

# Get state

v_stack_state = ctx.panel.state.v_stack

h_stack_state = v_stack_state["h_stack"] if v_stack_state is not None else None

count = h_stack_state["count"] if h_stack_state is not None else 0

# Add a message to the horizontal stack object with the name 'count'

# key: 'v_stack.h_stack.count'

h_stack.message("count", f"Count: {count}")

# Add a button to the horizontal stack object with the name 'increment'

# key: 'v_stack.h_stack.increment'

h_stack.btn(

"increment",

label="Increment",

icon="add",

on_click=self.increment,

variant="contained",

)

# Add a button to the horizontal stack object with the name 'decrement'

# key: 'v_stack.h_stack.count'

h_stack.btn(

"decrement",

label="Decrement",

icon="remove",

on_click=self.decrement,

variant="contained",

)

return types.Property(panel)

Panel state ¶¶

Panel state is included in every

render() call and event

callback and is analogous to operator parameters:

-

The values of any components defined in a panel’s

render()method are available via corresponding state properties of the same name -

The current panel state is readable during a panel’s execution

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

menu = panel.menu("menu", ...)

actions = menu.btn_group("actions")

actions.enum(

"mode",

values=["foo", "bar"],

on_change=self.on_change_mode,

...

)

panel.str("user_input", default="spam")

def on_change_mode(self, ctx):

# Object-based interface

mode = ctx.panel.state.menu.actions.mode

user_input = ctx.panel.state.user_input

# Functional interface

mode = ctx.panel.get_state("menu.actions.mode")

user_input = ctx.panel.get_state("user_input")

Panel state can be programmatically updated in panel methods via the two syntaxes shown below:

def on_change_view(self, ctx):

# Top-level state attributes can be modified by setting properties

ctx.panel.state.foo = "bar"

# Use set_state() to efficiently apply nested updates

ctx.panel.set_state("foo.bar", {"spam": "eggs"})

Warning

Don’t directly modify panel state in

render(), just like how

setState() should not be called in

React’s

render().

Instead set panel state in event callbacks as demonstrated above.

Panel data ¶¶

Panel data is designed to store larger content such as plot data that is loaded once and henceforward stored only clientside to avoid unnecessary/expensive reloads and serverside serialization during the lifecycle of the panel.

def on_load(self, ctx):

self.update_plot_data(ctx)

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

menu = panel.menu("menu", ...)

actions = menu.btn_group("actions")

actions.enum(

"brain_key",

label="Brain key",

values=["foo", "bar"],

default=None,

on_change=self.update_plot_data,

)

panel.plot("embeddings", config=..., layout=...)

return types.Property(panel)

def update_plot_data(self, ctx):

brain_key = ctx.panel.state.menu.actions.brain_key

if brain_key is None:

return

# Load expensive content based on current `brain_key`

results = ctx.dataset.load_brain_results(brain_key)

# Store large content as panel data for efficiency

data = {"points": results.points, ...}

ctx.panel.set_data("embeddings", data)

Note how the panel’s on_load() hook is implemented so that panel data can be

hydrated when the panel is initially loaded, and then subsequently plot data is

loaded only when the brain_key property is modified.

Note

Panel data is never readable in Python; it is only implicitly used by the types you define when they are rendered clientside.

Execution store ¶¶

Panels can store data in the execution store, which is a key-value store that is persisted beyond the lifetime of the panel. This is useful for storing information that should persist across panel instances and App sessions, such as cached data, long-lived panel state, or user preferences.

You can create/retrieve execution stores scoped to the current ctx.dataset

via ctx.store:

def on_load(ctx):

# Retrieve a store scoped to the current `ctx.dataset`

# The store is automatically created if necessary

store = ctx.store("my_store")

# Load a pre-existing value from the store

user_choice = store.get("user_choice")

# Store data with a TTL to ensure it is evicted after `ttl` seconds

store.set("my_key", {"foo": "bar"}, ttl=60)

# List all keys in the store

print(store.list_keys()) # ["user_choice", "my_key"]

# Retrieve data from the store

print(store.get("my_key")) # {"foo": "bar"}

# Retrieve metadata about a key

print(store.get_metadata("my_key"))

# {"created_at": ..., "updated_at": ..., "expires_at": ...}

# Delete a key from the store

store.delete("my_key")

# Clear all data in the store

store.clear()

Note

Did you know? Any execution stores associated with a dataset are automatically deleted when the dataset is deleted.

For advanced use cases, it is also possible to create and use global stores

that are available to all datasets via the

ExecutionStore class:

from fiftyone.operators import ExecutionStore

# Retrieve a global store

# The store is automatically created if necessary

store = ExecutionStore.create("my_store")

# Store data with a TTL to ensure it is evicted after `ttl` seconds

store.set("my_key", {"foo": "bar"}, ttl=60)

# List all keys in the global store

print(store.list_keys()) # ["my_key"]

# Retrieve data from the global store

print(store.get("my_key")) # {"foo": "bar"}

# Retrieve metadata about a key

print(store.get_metadata("my_key"))

# {"created_at": ..., "updated_at": ..., "expires_at": ...}

# Delete a key from the global store

store.delete("my_key")

# Clear all data in the global store

store.clear()

Warning

Global stores have no automatic garbage collection, so take care when creating and using global stores whose keys do not utilize TTLs.

Saved workspaces ¶¶

Saved workspaces may contain any number of Python panels!

When a workspace is saved, the current panel state of any panels in the layout is persisted as part of the workspace’s definition. Thus when the workspace is loaded later, all panels will “remember” their state.

Panel data (which may be large), on the other hand, is not explicitly persisted. Instead it should be hydrated when the panel is loaded using the pattern demonstrated here.

Accessing secrets ¶¶

Panels can access secrets defined by their plugin.

At runtime, the panel’s execution context

is automatically hydrated with any available secrets that are declared by the

plugin. Panels can access these secrets via the ctx.secrets dict:

def on_load(self, ctx):

url = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_URL"]

username = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_USERNAME"]

password = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_PASSWORD"]

email = ctx.secrets["FIFTYONE_CVAT_EMAIL"]

Common patterns ¶¶

Most panels make use of common patterns like callbacks, menus, interactive plots, and walkthrough layouts.

Learning the patterns described below will help you build panels faster and avoid roadblocks along the way.

Note

Check out the panel examples plugin to see a collection of fully-functional panels that demonstrate the common patterns below.

Callbacks ¶¶

Most panel components support callback methods like on_click and on_change

that you can implement to perform operations and trigger state updates when

users interact with the components.

For example, the code below shows how clicking a button or changing the state of a slider can initiate callbacks that trigger operators, open other panels, and programmatically modify the current state.

Note

All callback functions have access to the current

ExecutionContext

via their ctx argument and can use it to get/update panel state and

trigger other operations.

def on_load(self, ctx):

# Set initial slider state

ctx.panel.state.slider_value = 5

def open_compute(self, ctx):

# Launch an interactive prompt for user to execute an operator

ctx.prompt("@voxel51/brain/compute_visualization")

def open_embeddings(self, ctx):

# Open embeddings panel

ctx.trigger("open_panel", params=dict(name="Embeddings"))

def change_value(self, ctx):

# Grab current slider value from `ctx.params`

ctx.panel.state.slider_value = (

ctx.params["value"] or ctx.params["panel_state"]["slider_value"]

)

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

# Define buttons that work with on_click callbacks

panel.btn(

"button_1",

label="Compute visualization",

on_click=self.open_compute,

)

panel.btn(

"button_2",

label="Open embeddings panel",

on_click=self.open_embeddings,

)

# Define a slider with an `on_change` callback

slider = types.SliderView(

data=ctx.panel.state.slider_value, label="Example Slider"

)

schema = {"min": 0, "max": 10, "multipleOf": 1}

panel.int(

"slider_value", view=slider, on_change=self.change_value, **schema

)

Note

Did you know? You can use ctx.params in a callback to access the state

of the property that triggered the action.

Dropdown menus ¶¶

Dropdown menus can be a useful tool to build panels whose layout/content dynamically changes based on the current state of the menu.

Here’s an example of a dropdown menu with selectable options that alters the panel layout based on user input.

Note

Panels also support a menu() property that provides a convenient syntax

for defining a group of dropdowns, buttons, etc that can be anchored

to a particular position in your panel (e.g., top-left).

Check out this section for an example panel that

makes use of menu().

class DropdownMenuExample(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

name="example_dropdown_menu",

label="Examples: Dropdown Menu",

)

def on_load(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.selection = None

def alter_selection(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.selection = ctx.params["value"]

def refresh_page(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.reload_dataset()

def reload_samples(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.reload_samples()

def say_hi(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.notify("Hi!", variant="success")

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

panel.md(

"""

### Welcome to the Python Panel Dropdown Menu Example

Use the menu below to select what you would like to do next!

---

""",

name="header",

width=50, # 50% of current panel width

height="200px",

)

# Define a dropdown menu and add choices

dropdown = types.DropdownView()

dropdown.add_choice(

"refresh",

label="Display Refresh Button",

description="Displays button that will refresh the FiftyOne App",

)

dropdown.add_choice(

"reload_samples",

label="Display Reload Samples Button",

description="Displays button that will reload the samples view",

)

dropdown.add_choice(

"say_hi",

label="Display Hi Button",

description="Displays button that will say hi",

)

# Add dropdown menu to the panel as a view and use the `on_change`

# callback to trigger `alter_selection`

panel.view(

"dropdown",

view=dropdown,

label="Dropdown Menu",

on_change=self.alter_selection,

)

# Change panel visual state dependent on dropdown menu selection

if ctx.panel.state.selection == "refresh":

panel.btn(

"refresh",

label="Refresh FiftyOne",

on_click=self.refresh_page,

variant="contained",

)

elif ctx.panel.state.selection == "reload_samples":

panel.btn(

"reload_samples",

label="Reload Samples",

on_click=self.reload_samples,

variant="contained",

)

elif ctx.panel.state.selection == "say_hi":

panel.btn(

"say_hi",

label="Say Hi",

on_click=self.say_hi,

variant="contained",

)

return types.Property(

panel,

view=types.GridView(

height=100,

width=100,

align_x="center",

align_y="center",

orientation="vertical",

),

)

Interactive plots ¶¶

Panels provide native support for defining interactive plots that can render data from the current dataset and dynamically update or trigger actions as users interact with the plots.

For example, here’s a panel that displays a histogram of a specified field of the current dataset where clicking a bar loads the corresponding samples in the App.

import fiftyone.operators as foo

import fiftyone.operators.types as types

from fiftyone import ViewField as F

class InteractivePlotExample(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

name="example_interactive_plot",

label="Examples: Interactive Plot",

icon="bar_chart",

)

def on_load(self, ctx):

# Get target field

target_field = (

ctx.panel.state.target_field or "ground_truth.detections.label"

)

ctx.panel.state.target_field = target_field

# Compute target histogram for current dataset

counts = ctx.dataset.count_values(target_field)

keys, values = zip(*sorted(counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[0]))

# Store as panel data for efficiency

ctx.panel.data.histogram = {"x": keys, "y": values, "type": "bar"}

# Launch panel in a horizontal split view

ctx.ops.split_panel("example_interactive_plot", layout="horizontal")

def on_change_view(self, ctx):

# Update histogram when current view changes

self.on_load(ctx)

def on_histogram_click(self, ctx):

# The histogram bar that the user clicked

value = ctx.params.get("x")

# Create a view that matches the selected histogram bar

field = ctx.panel.state.target_field

view = _make_matching_view(ctx.dataset, field, value)

# Load view in App

if view is not None:

ctx.ops.set_view(view=view)

def reset(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.clear_view()

self.on_load(ctx)

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

panel.plot(

"histogram",

layout={

"title": {

"text": "Interactive Histogram",

"xanchor": "center",

"yanchor": "top",

"automargin": True,

},

"xaxis": {"title": "Labels"},

"yaxis": {"title": "Count"},

},

on_click=self.on_histogram_click,

width=100,

)

panel.btn(

"reset",

label="Reset Chart",

on_click=self.reset,

variant="contained",

)

return types.Property(

panel,

view=types.GridView(

align_x="center",

align_y="center",

orientation="vertical",

height=100,

width=100,

gap=2,

padding=0,

),

)

def _make_matching_view(dataset, field, value):

if field.endswith(".label"):

root_field = field.split(".")[0]

return dataset.filter_labels(root_field, F("label") == value)

elif field == "tags":

return dataset.match_tags(value)

else:

return dataset.match(F(field) == value)

Walkthroughs ¶¶

You can use a combination of panel objects like markdown, buttons, arrow navigation, and layout containers to create guided walkthroughs similar to the ones at try.fiftyone.ai.

Here’s an example of a panel that leads the user through multiple steps of a guided workflow.

class WalkthroughExample(foo.Panel):

@property

def config(self):

return foo.PanelConfig(

name="example_walkthrough",

label="Examples: Walkthrough",

)

def on_load(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.page = 1

info_table = [\

{\

"Dataset Name": f"{ctx.dataset.name}",\

"Dataset Description": "FiftyOne Quick Start Zoo Dataset",\

"Number of Samples": f"{ctx.dataset.count()}",\

},\

]

ctx.panel.state.info_table = info_table

def go_to_next_page(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.page = ctx.panel.state.page + 1

def go_to_previous_page(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.page = ctx.panel.state.page - 1

def reset_page(self, ctx):

ctx.panel.state.page = 1

def open_operator_io(self, ctx):

ctx.ops.open_panel("OperatorIO")

def render(self, ctx):

panel = types.Object()

# Define a vertical stack to live inside your panel

stack = panel.v_stack(

"welcome", gap=2, width=75, align_x="center", align_y="center"

)

button_container = types.GridView(

gap=2, align_x="left", align_y="center"

)

page = ctx.panel.state.get("page", 1)

if page == 1:

stack.md(

"""

### A Tutorial Walkthrough

Welcome to the FiftyOne App! Here is a great example of what it looks like to create a tutorial style walkthrough via a Python Panel.

""",

name="markdown_screen_1",

)

stack.media_player(

"video",

"https://youtu.be/ad79nYk2keg",

align_x="center",

align_y="center",

)

elif page == 2:

stack.md(

"""

### Information About Your Dataset

Perhaps you would like to know some more information about your dataset?

""",

name="markdown_screen_2",

)

table = types.TableView()

table.add_column("Dataset Name", label="Dataset Name")

table.add_column("Dataset Description", label="Description")

table.add_column("Number of Samples", label="Number of Samples")

panel.obj(

name="info_table",

view=table,

label="Cool Info About Your Data",

)

elif page == 3:

if ctx.panel.state.operator_status != "opened":

stack.md(

"""

### One Last Trick

If you want to do something cool, click the button below.

""",

name="markdown_screen_3",

)

btns = stack.obj("top_btns", view=button_container)

btns.type.btn(

"open_operator_io",

label="Do Something Cool",

on_click=self.open_operator_io,

variant="contained"

)

else:

stack.md(

"""

#### How did you get here?

Looks like you found the end of the walkthrough. Or have you gotten a little lost in the grid? No worries, let's get you back to the walkthrough!

"""

)

btns = stack.obj("btns", view=button_container)

btns.type.btn("reset", label="Go Home", on_click=self.reset_page)

# Arrow navigation to go to next or previous page

panel.arrow_nav(

"arrow_nav",

forward=page != 3, # hidden for the last page

backward=page != 1, # hidden for the first page

on_forward=self.go_to_next_page,

on_backward=self.go_to_previous_page,

)

return types.Property(

panel,

view=types.GridView(

height=100, width=100, align_x="center", align_y="center"

),

)

Displaying multimedia ¶¶

Displaying images, videos, and other forms of multimedia is straightforward in panels. You can embed third-party resources like URLs or load multimedia stored in local directories.

Here are some examples of panels that load, render, and manipulate various forms of image and video data.

Type hints ¶¶

Defining the types of your panel’s function arguments allows you to inspect the methods available to an object and will dramatically help you increase your speed of development.