Using FiftyOne Datasets ¶¶

After a Dataset has been loaded or created, FiftyOne provides powerful

functionality to inspect, search, and modify it from a Dataset-wide down to

a Sample level.

The following sections provide details of how to use various aspects of a

FiftyOne Dataset.

Datasets ¶¶

Instantiating a Dataset object creates a new dataset.

import fiftyone as fo

dataset1 = fo.Dataset("my_first_dataset")

dataset2 = fo.Dataset("my_second_dataset")

dataset3 = fo.Dataset() # generates a default unique name

Check to see what datasets exist at any time via list_datasets():

print(fo.list_datasets())

# ['my_first_dataset', 'my_second_dataset', '2020.08.04.12.36.29']

Load a dataset using

load_dataset().

Dataset objects are singletons. Cool!

_dataset2 = fo.load_dataset("my_second_dataset")

_dataset2 is dataset2 # True

If you try to load a dataset via Dataset(...) or create a new dataset via

load_dataset() you’re going to

have a bad time:

_dataset2 = fo.Dataset("my_second_dataset")

# Dataset 'my_second_dataset' already exists; use `fiftyone.load_dataset()`

# to load an existing dataset

dataset4 = fo.load_dataset("my_fourth_dataset")

# DoesNotExistError: Dataset 'my_fourth_dataset' not found

Dataset media type ¶¶

The media type of a dataset is determined by the

media type of the Sample objects that it contains.

The media_type property of a

dataset is set based on the first sample added to it:

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

print(dataset.media_type)

# None

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

dataset.add_sample(sample)

print(dataset.media_type)

# "image"

Note that datasets are homogeneous; they must contain samples of the same media type (except for grouped datasets):

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/video.mp4")

dataset.add_sample(sample)

# MediaTypeError: Sample media type 'video' does not match dataset media type 'image'

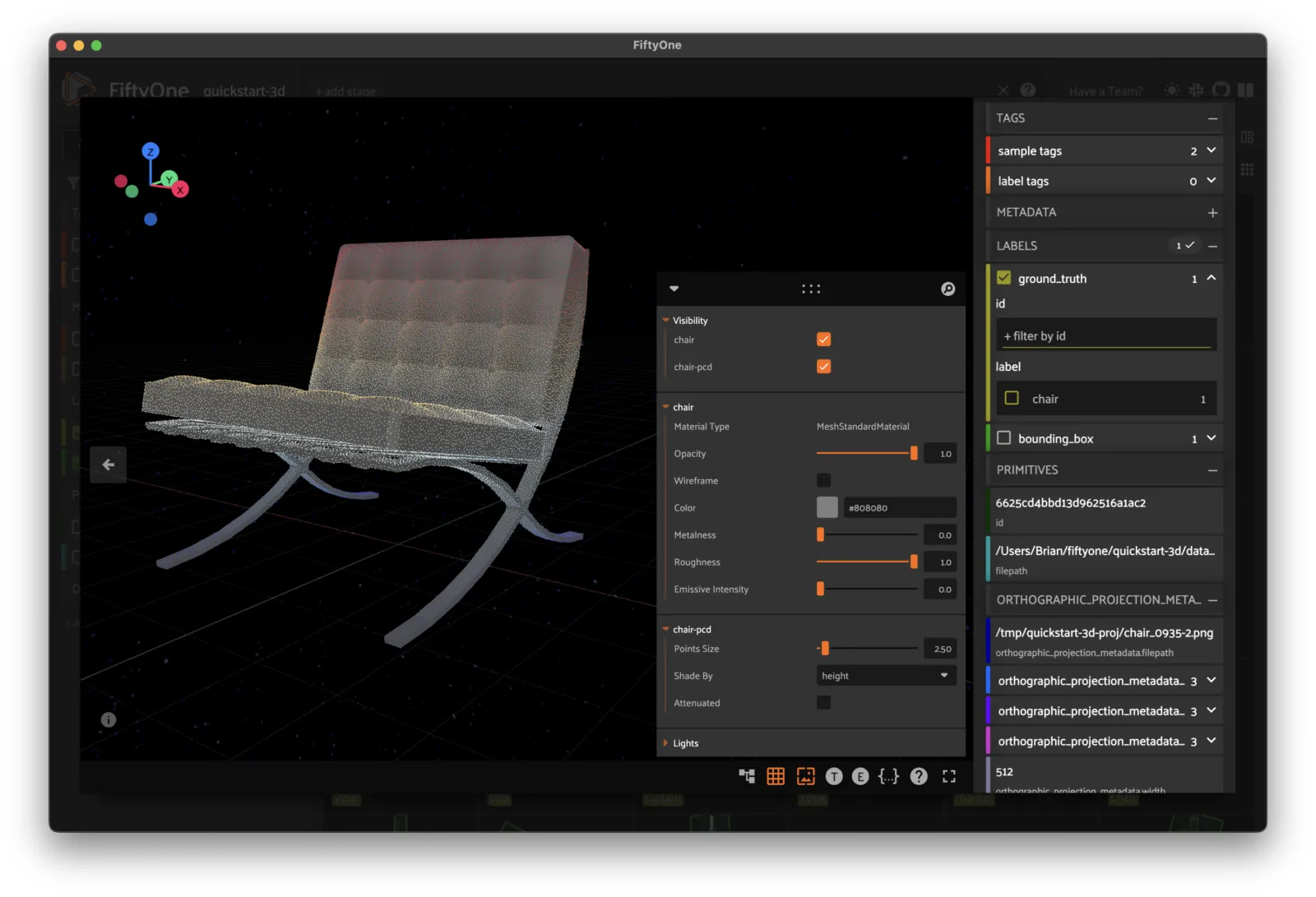

The following media types are available:

| Media type | Description |

|---|---|

image |

Datasets that contain images |

video |

Datasets that contain videos |

3d |

Datasets that contain 3D scenes |

point-cloud |

Datasets that contain point clouds |

group |

Datasets that contain grouped data slices |

Dataset persistence ¶¶

By default, datasets are non-persistent. Non-persistent datasets are deleted from the database each time the database is shut down. Note that FiftyOne does not store the raw data in datasets directly (only the labels), so your source files on disk are untouched.

To make a dataset persistent, set its

persistent property to

True:

# Make the dataset persistent

dataset1.persistent = True

Without closing your current Python shell, open a new shell and run:

import fiftyone as fo

# Verify that both persistent and non-persistent datasets still exist

print(fo.list_datasets())

# ['my_first_dataset', 'my_second_dataset', '2020.08.04.12.36.29']

All three datasets are still available, since the database connection has not been terminated.

However, if you exit all processes with fiftyone imported, then open a new

shell and run the command again:

import fiftyone as fo

# Verify that non-persistent datasets have been deleted

print(fo.list_datasets())

# ['my_first_dataset']

you’ll see that the my_second_dataset and 2020.08.04.12.36.29 datasets have

been deleted because they were not persistent.

Dataset version ¶¶

The version of the fiftyone package for which a dataset is formatted is

stored in the version property

of the dataset.

If you upgrade your fiftyone package and then load a dataset that was created

with an older version of the package, it will be automatically migrated to the

new package version (if necessary) the first time you load it.

Dataset tags ¶¶

All Dataset instances have a

tags property that you can use to

store an arbitrary list of string tags.

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Add some tags

dataset.tags = ["test", "projectA"]

# Edit the tags

dataset.tags.pop()

dataset.tags.append("projectB")

dataset.save() # must save after edits

Note

You must call

dataset.save() after updating

the dataset’s tags property

in-place to save the changes to the database.

Dataset stats ¶¶

You can use the stats() method on

a dataset to obtain information about the size of the dataset on disk,

including its metadata in the database and optionally the size of the physical

media on disk:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart")

fo.pprint(dataset.stats(include_media=True))

{

'samples_count': 200,

'samples_bytes': 1290762,

'samples_size': '1.2MB',

'media_bytes': 24412374,

'media_size': '23.3MB',

'total_bytes': 25703136,

'total_size': '24.5MB',

}

You can also invoke

stats() on a

dataset view to retrieve stats for a specific subset of

the dataset:

view = dataset[:10].select_fields("ground_truth")

fo.pprint(view.stats(include_media=True))

{

'samples_count': 10,

'samples_bytes': 10141,

'samples_size': '9.9KB',

'media_bytes': 1726296,

'media_size': '1.6MB',

'total_bytes': 1736437,

'total_size': '1.7MB',

}

Storing info ¶¶

All Dataset instances have an

info property, which contains a

dictionary that you can use to store any JSON-serializable information you wish

about your dataset.

Datasets can also store more specific types of ancillary information such as class lists and mask targets.

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Store a class list in the dataset's info

dataset.info = {

"dataset_source": "https://...",

"author": "...",

}

# Edit existing info

dataset.info["owner"] = "..."

dataset.save() # must save after edits

Note

You must call

dataset.save() after updating

the dataset’s info property

in-place to save the changes to the database.

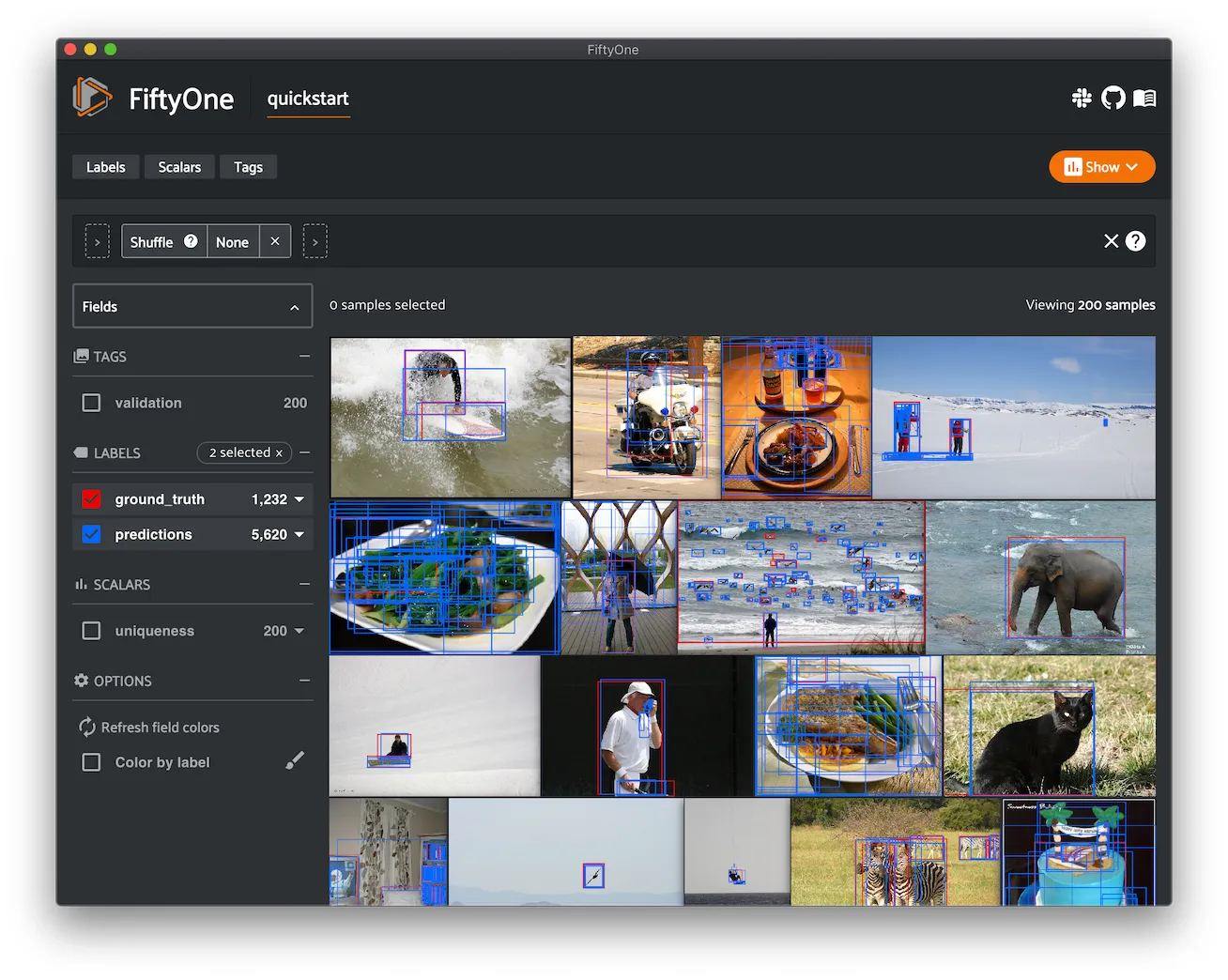

Dataset App config ¶¶

All Dataset instances have an

app_config property that

contains a DatasetAppConfig that you can use to store dataset-specific

settings that customize how the dataset is visualized in the

FiftyOne App.

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart")

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

# View the dataset's current App config

print(dataset.app_config)

Multiple media fields ¶¶

You can declare multiple media fields on a dataset and configure which field is used by various components of the App by default:

import fiftyone.utils.image as foui

# Generate some thumbnail images

foui.transform_images(

dataset,

size=(-1, 32),

output_field="thumbnail_path",

output_dir="/tmp/thumbnails",

)

# Configure when to use each field

dataset.app_config.media_fields = ["filepath", "thumbnail_path"]

dataset.app_config.grid_media_field = "thumbnail_path"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

session.refresh()

You can set media_fallback=True if you want the App to fallback to the

filepath field if an alternate media field is missing for a particular

sample in the grid and/or modal:

# Fallback to `filepath` if an alternate media field is missing

dataset.app_config.media_fallback = True

dataset.save()

Custom color scheme ¶¶

You can store a custom color scheme on a dataset that should be used by default whenever the dataset is loaded in the App:

dataset.evaluate_detections(

"predictions", gt_field="ground_truth", eval_key="eval"

)

# Store a custom color scheme

dataset.app_config.color_scheme = fo.ColorScheme(

color_pool=["#ff0000", "#00ff00", "#0000ff", "pink", "yellowgreen"],

color_by="value",

fields=[\

{\

"path": "ground_truth",\

"colorByAttribute": "eval",\

"valueColors": [\

{"value": "fn", "color": "#0000ff"}, # false negatives: blue\

{"value": "tp", "color": "#00ff00"}, # true positives: green\

]\

},\

{\

"path": "predictions",\

"colorByAttribute": "eval",\

"valueColors": [\

{"value": "fp", "color": "#ff0000"}, # false positives: red\

{"value": "tp", "color": "#00ff00"}, # true positives: green\

]\

}\

]

)

dataset.save() # must save after edits

# Setting `color_scheme` to None forces the dataset's default color scheme

# to be loaded

session.color_scheme = None

Note

Refer to the ColorScheme class for documentation of the available

customization options.

Note

Did you know? You can also configure color schemes directly in the App!

Sidebar groups ¶¶

You can configure the organization and default expansion state of the sidebar’s field groups:

# Get the default sidebar groups for the dataset

sidebar_groups = fo.DatasetAppConfig.default_sidebar_groups(dataset)

# Collapse the `metadata` section by default

print(sidebar_groups[2].name) # metadata

sidebar_groups[2].expanded = False

# Modify the dataset's App config

dataset.app_config.sidebar_groups = sidebar_groups

dataset.save() # must save after edits

session.refresh()

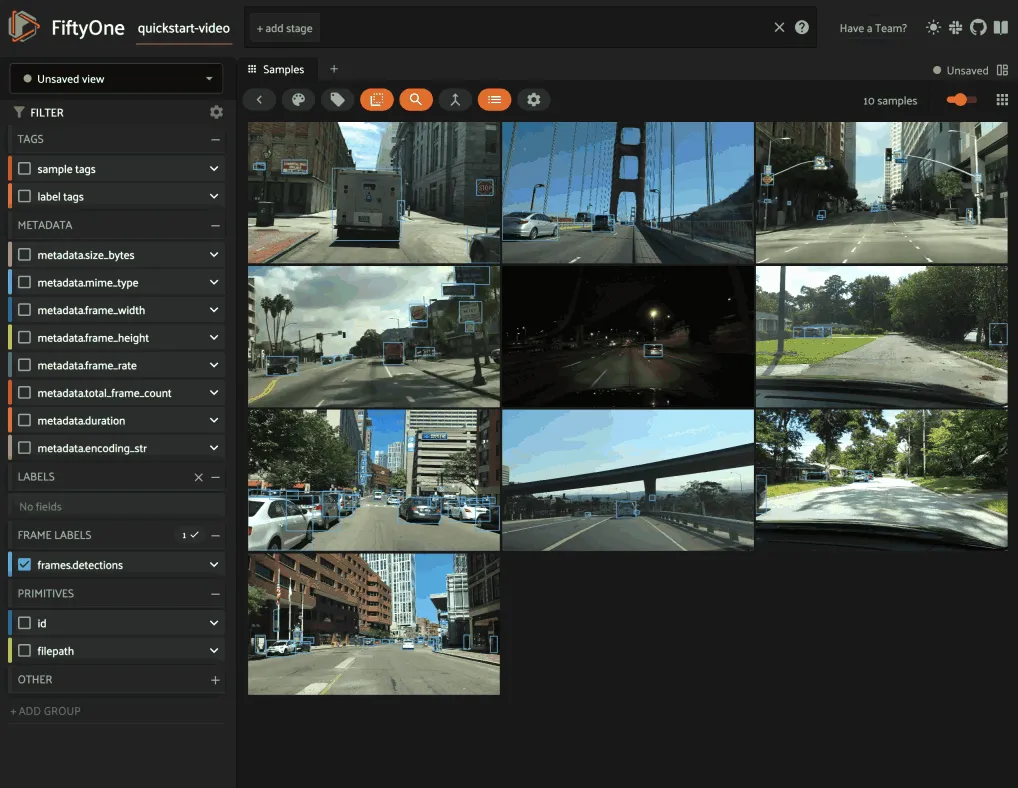

Disable frame filtering ¶¶

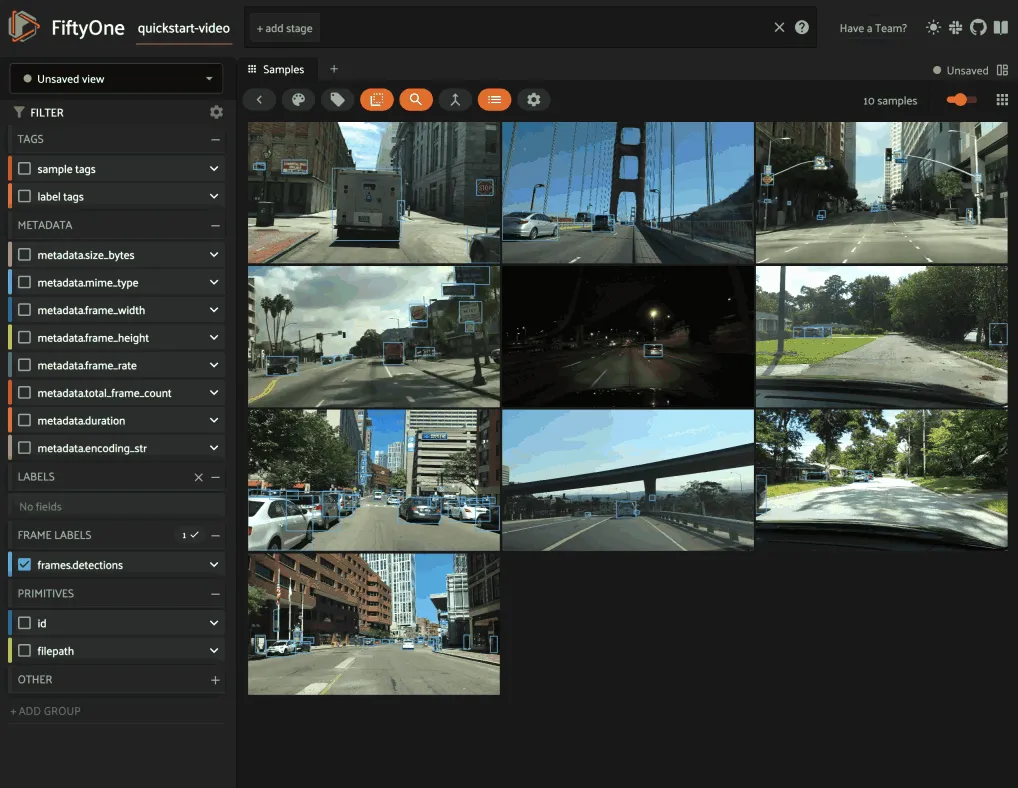

Filtering by frame-level fields of video datasets in the App’s grid view can be expensive when the dataset is large.

You can disable frame filtering for a video dataset as follows:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart-video")

dataset.app_config.disable_frame_filtering = True

dataset.save() # must save after edits

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

Note

Did you know? You can also globally disable frame filtering for all video datasets via your App config.

Resetting a dataset’s App config ¶¶

You can conveniently reset any property of a dataset’s App config by setting it

to None:

# Reset the dataset's color scheme

dataset.app_config.color_scheme = None

dataset.save() # must save after edits

print(dataset.app_config)

session.refresh()

or you can reset the entire App config by setting the

app_config property to

None:

# Reset App config

dataset.app_config = None

print(dataset.app_config)

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

Note

Check out this section for more information about customizing the behavior of the App.

Storing class lists ¶¶

All Dataset instances have

classes and

default_classes

properties that you can use to store the lists of possible classes for your

annotations/models.

The classes property is a

dictionary mapping field names to class lists for a single Label field of the

dataset.

If all Label fields in your dataset have the same semantics, you can store a

single class list in the store a single target dictionary in the

default_classes

property of your dataset.

You can also pass your class lists to methods such as

evaluate_classifications(),

evaluate_detections(),

and export() that

require knowledge of the possible classes in a dataset or field(s).

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Set default classes

dataset.default_classes = ["cat", "dog"]

# Edit the default classes

dataset.default_classes.append("other")

dataset.save() # must save after edits

# Set classes for the `ground_truth` and `predictions` fields

dataset.classes = {

"ground_truth": ["cat", "dog"],

"predictions": ["cat", "dog", "other"],

}

# Edit a field's classes

dataset.classes["ground_truth"].append("other")

dataset.save() # must save after edits

Note

You must call

dataset.save() after updating

the dataset’s classes and

default_classes

properties in-place to save the changes to the database.

Storing mask targets ¶¶

All Dataset instances have

mask_targets and

default_mask_targets

properties that you can use to store label strings for the pixel values of

Segmentation field masks.

The mask_targets property

is a dictionary mapping field names to target dicts, each of which is a

dictionary defining the mapping between pixel values (2D masks) or RGB hex

strings (3D masks) and label strings for the Segmentation masks in the

specified field of the dataset.

If all Segmentation fields in your dataset have the same semantics, you can

store a single target dictionary in the

default_mask_targets

property of your dataset.

When you load datasets with Segmentation fields in the App that have

corresponding mask targets, the label strings will appear in the App’s tooltip

when you hover over pixels.

You can also pass your mask targets to methods such as

evaluate_segmentations()

and export() that

require knowledge of the mask targets for a dataset or field(s).

If you are working with 2D segmentation masks, specify target keys as integers:

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Set default mask targets

dataset.default_mask_targets = {1: "cat", 2: "dog"}

# Edit the default mask targets

dataset.default_mask_targets[255] = "other"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

# Set mask targets for the `ground_truth` and `predictions` fields

dataset.mask_targets = {

"ground_truth": {1: "cat", 2: "dog"},

"predictions": {1: "cat", 2: "dog", 255: "other"},

}

# Edit an existing mask target

dataset.mask_targets["ground_truth"][255] = "other"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

If you are working with RGB segmentation masks, specify target keys as RGB hex strings:

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Set default mask targets

dataset.default_mask_targets = {"#499CEF": "cat", "#6D04FF": "dog"}

# Edit the default mask targets

dataset.default_mask_targets["#FF6D04"] = "person"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

# Set mask targets for the `ground_truth` and `predictions` fields

dataset.mask_targets = {

"ground_truth": {"#499CEF": "cat", "#6D04FF": "dog"},

"predictions": {

"#499CEF": "cat", "#6D04FF": "dog", "#FF6D04": "person"

},

}

# Edit an existing mask target

dataset.mask_targets["ground_truth"]["#FF6D04"] = "person"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

Note

You must call

dataset.save() after updating

the dataset’s

mask_targets and

default_mask_targets

properties in-place to save the changes to the database.

Storing keypoint skeletons ¶¶

All Dataset instances have

skeletons and

default_skeleton

properties that you can use to store keypoint skeletons for Keypoint field(s)

of a dataset.

The skeletons property is a

dictionary mapping field names to KeypointSkeleton instances, each of which

defines the keypoint label strings and edge connectivity for the Keypoint

instances in the specified field of the dataset.

If all Keypoint fields in your dataset have the same semantics, you can store

a single KeypointSkeleton in the

default_skeleton

property of your dataset.

When you load datasets with Keypoint fields in the App that have

corresponding skeletons, the skeletons will automatically be rendered and label

strings will appear in the App’s tooltip when you hover over the keypoints.

Keypoint skeletons can be associated with Keypoint or Keypoints fields

whose points attributes all

contain a fixed number of semantically ordered points.

The edges argument

contains lists of integer indexes that define the connectivity of the points in

the skeleton, and the optional

labels argument

defines the label strings for each node in the skeleton.

For example, the skeleton below is defined by edges between the following nodes:

left hand <-> left shoulder <-> right shoulder <-> right hand

left eye <-> right eye <-> mouth

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

# Set keypoint skeleton for the `ground_truth` field

dataset.skeletons = {

"ground_truth": fo.KeypointSkeleton(

labels=[\

"left hand" "left shoulder", "right shoulder", "right hand",\

"left eye", "right eye", "mouth",\

],

edges=[[0, 1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6]],

)

}

# Edit an existing skeleton

dataset.skeletons["ground_truth"].labels[-1] = "lips"

dataset.save() # must save after edits

Note

When using keypoint skeletons, each Keypoint instance’s

points list must always

respect the indexing defined by the field’s KeypointSkeleton.

If a particular keypoint is occluded or missing for an object, use

[float("nan"), float("nan")] in its

points list.

Note

You must call

dataset.save() after updating

the dataset’s

skeletons and

default_skeleton

properties in-place to save the changes to the database.

Deleting a dataset ¶¶

Delete a dataset explicitly via

Dataset.delete(). Once a dataset

is deleted, any existing reference in memory will be in a volatile state.

Dataset.name and

Dataset.deleted will still be valid

attributes, but calling any other attribute or method will raise a

DoesNotExistError.

dataset = fo.load_dataset("my_first_dataset")

dataset.delete()

print(fo.list_datasets())

# []

print(dataset.name)

# my_first_dataset

print(dataset.deleted)

# True

print(dataset.persistent)

# DoesNotExistError: Dataset 'my_first_dataset' is deleted

Samples ¶¶

An individual Sample is always initialized with a filepath to the

corresponding data on disk.

# An image sample

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

# A video sample

another_sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/video.mp4")

Note

Creating a new Sample does not load the source data into memory. Source

data is read only as needed by the App.

Adding samples to a dataset ¶¶

A Sample can easily be added to an existing Dataset:

dataset = fo.Dataset("example_dataset")

dataset.add_sample(sample)

When a sample is added to a dataset, the relevant attributes of the Sample

are automatically updated:

print(sample.in_dataset)

# True

print(sample.dataset_name)

# example_dataset

Every sample in a dataset is given a unique ID when it is added:

print(sample.id)

# 5ee0ebd72ceafe13e7741c42

Multiple samples can be efficiently added to a dataset in batches:

print(len(dataset))

# 1

dataset.add_samples(

[\

fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image1.jpg"),\

fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image2.jpg"),\

fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image3.jpg"),\

]

)

print(len(dataset))

# 4

Accessing samples in a dataset ¶¶

FiftyOne provides multiple ways to access a Sample in a Dataset.

You can iterate over the samples in a dataset:

for sample in dataset:

print(sample)

Use first() and

last() to retrieve the first and

last samples in a dataset, respectively:

first_sample = dataset.first()

last_sample = dataset.last()

Samples can be accessed directly from datasets by their IDs or their filepaths.

Sample objects are singletons, so the same Sample instance is returned

whenever accessing the sample from the Dataset:

same_sample = dataset[sample.id]

print(same_sample is sample)

# True

also_same_sample = dataset[sample.filepath]

print(also_same_sample is sample)

# True

You can use dataset views to perform more sophisticated operations on samples like searching, filtering, sorting, and slicing.

Note

Accessing a sample by its integer index in a Dataset is not allowed. The

best practice is to lookup individual samples by ID or filepath, or use

array slicing to extract a range of samples, and iterate over samples in a

view.

dataset[0]

# KeyError: Accessing dataset samples by numeric index is not supported.

# Use sample IDs, filepaths, slices, boolean arrays, or a boolean ViewExpression instead

Deleting samples from a dataset ¶¶

Samples can be removed from a Dataset through their ID, either one at a time

or in batches via

delete_samples():

dataset.delete_samples(sample_id)

# equivalent to above

del dataset[sample_id]

dataset.delete_samples([sample_id1, sample_id2])

Samples can also be removed from a Dataset by passing Sample instance(s)

or DatasetView instances:

# Remove a random sample

sample = dataset.take(1).first()

dataset.delete_samples(sample)

# Remove 10 random samples

view = dataset.take(10)

dataset.delete_samples(view)

If a Sample object in memory is deleted from a dataset, it will revert to

a Sample that has not been added to a Dataset:

print(sample.in_dataset)

# False

print(sample.dataset_name)

# None

print(sample.id)

# None

Fields ¶¶

A Field is an attribute of a Sample that stores information about the

sample.

Fields can be dynamically created, modified, and deleted from samples on a

per-sample basis. When a new Field is assigned to a Sample in a Dataset,

it is automatically added to the dataset’s schema and thus accessible on all

other samples in the dataset.

If a field exists on a dataset but has not been set on a particular sample, its

value will be None.

Default sample fields ¶¶

By default, all Sample instances have the following fields:

| Field | Type | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

id |

string | None |

The ID of the sample in its parent dataset, which is generated automatically when the sample is added to a dataset, or None if the sample doesnot belong to a dataset |

filepath |

string | REQUIRED | The path to the source data on disk. Must be provided at sample creation time |

media_type |

string | N/A | The media type of the sample. Computed automatically from the provided filepath |

tags |

list | [] |

A list of string tags for the sample |

metadata |

Metadata |

None |

Type-specific metadata about the source data |

created_at |

datetime | None |

The datetime that the sample was added to its parent dataset, which is generated automatically, or None if the sample does not belong to adataset |

last_modified_at |

datetime | None |

The datetime that the sample was last modified, which is updated automatically, or None if thesample does not belong to a dataset |

Note

The created_at and last_modified_at fields are

read-only and are automatically populated/updated

when you add samples to datasets and modify them, respectively.

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

}>

Accessing fields of a sample ¶¶

The names of available fields can be checked on any individual Sample:

sample.field_names

# ('id', 'filepath', 'tags', 'metadata', 'created_at', 'last_modified_at')

The value of a Field for a given Sample can be accessed either by either

attribute or item access:

sample.filepath

sample["filepath"] # equivalent

Field schemas ¶¶

You can use

get_field_schema() to

retrieve detailed information about the schema of the samples in a dataset:

dataset = fo.Dataset("a_dataset")

dataset.add_sample(sample)

dataset.get_field_schema()

OrderedDict([\

('id', <fiftyone.core.fields.ObjectIdField at 0x7fbaa862b358>),\

('filepath', <fiftyone.core.fields.StringField at 0x11c77ae10>),\

('tags', <fiftyone.core.fields.ListField at 0x11c790828>),\

('metadata', <fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField at 0x11c7907b8>),\

('created_at', <fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField at 0x7fea48361af0>),\

('last_modified_at', <fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField at 0x7fea48361b20>)]),

])

You can also view helpful information about a dataset, including its schema, by printing it:

print(dataset)

Name: a_dataset

Media type: image

Num samples: 1

Persistent: False

Tags: []

Sample fields:

id: fiftyone.core.fields.ObjectIdField

filepath: fiftyone.core.fields.StringField

tags: fiftyone.core.fields.ListField(fiftyone.core.fields.StringField)

metadata: fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField(fiftyone.core.metadata.ImageMetadata)

created_at: fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField

last_modified_at: fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField

Note

Did you know? You can store metadata such as descriptions on your dataset’s fields!

Adding fields to a sample ¶¶

New fields can be added to a Sample using item assignment:

sample["integer_field"] = 51

sample.save()

If the Sample belongs to a Dataset, the dataset’s schema will automatically

be updated to reflect the new field:

print(dataset)

Name: a_dataset

Media type: image

Num samples: 1

Persistent: False

Tags: []

Sample fields:

id: fiftyone.core.fields.ObjectIdField

filepath: fiftyone.core.fields.StringField

tags: fiftyone.core.fields.ListField(fiftyone.core.fields.StringField)

metadata: fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField(fiftyone.core.metadata.ImageMetadata)

created_at: fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField

last_modified_at: fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField

integer_field: fiftyone.core.fields.IntField

A Field can be any primitive type, such as bool, int, float, str,

date, datetime, list, dict, or more complex data structures

like label types:

sample["animal"] = fo.Classification(label="alligator")

sample.save()

Whenever a new field is added to a sample in a dataset, the field is available

on every other sample in the dataset with the value None.

Fields must have the same type (or None) across all samples in the dataset.

Setting a field to an inappropriate type raises an error:

sample2.integer_field = "a string"

sample2.save()

# ValidationError: a string could not be converted to int

Note

You must call sample.save() in

order to persist changes to the database when editing samples that are in

datasets.

Adding fields to a dataset ¶¶

You can also use

add_sample_field() to

declare new sample fields directly on datasets without explicitly populating

any values on its samples:

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(

filepath="image.jpg",

ground_truth=fo.Classification(label="cat"),

)

dataset = fo.Dataset()

dataset.add_sample(sample)

# Declare new primitive fields

dataset.add_sample_field("scene_id", fo.StringField)

dataset.add_sample_field("quality", fo.FloatField)

# Declare untyped list fields

dataset.add_sample_field("more_tags", fo.ListField)

dataset.add_sample_field("info", fo.ListField)

# Declare a typed list field

dataset.add_sample_field("also_tags", fo.ListField, subfield=fo.StringField)

# Declare a new Label field

dataset.add_sample_field(

"predictions",

fo.EmbeddedDocumentField,

embedded_doc_type=fo.Classification,

)

print(dataset.get_field_schema())

{

'id': <fiftyone.core.fields.ObjectIdField object at 0x7f9280803910>,

'filepath': <fiftyone.core.fields.StringField object at 0x7f92d273e0d0>,

'tags': <fiftyone.core.fields.ListField object at 0x7f92d2654f70>,

'metadata': <fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField object at 0x7f9280803d90>,

'created_at': <fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField object at 0x7fea48361af0>,

'last_modified_at': <fiftyone.core.fields.DateTimeField object at 0x7fea48361b20>,

'ground_truth': <fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField object at 0x7f92d2605190>,

'scene_id': <fiftyone.core.fields.StringField object at 0x7f9280803490>,

'quality': <fiftyone.core.fields.FloatField object at 0x7f92d2605bb0>,

'more_tags': <fiftyone.core.fields.ListField object at 0x7f92d08e4550>,

'info': <fiftyone.core.fields.ListField object at 0x7f92d264f9a0>,

'also_tags': <fiftyone.core.fields.ListField object at 0x7f92d264ff70>,

'predictions': <fiftyone.core.fields.EmbeddedDocumentField object at 0x7f92d2605640>,

}

Whenever a new field is added to a dataset, the field is immediately available

on all samples in the dataset with the value None:

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': '642d8848f291652133df8d3a',

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/Users/Brian/dev/fiftyone/image.jpg',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': datetime.datetime(2024, 7, 22, 5, 0, 25, 372399),

'last_modified_at': datetime.datetime(2024, 7, 22, 5, 0, 25, 372399),

'ground_truth': <Classification: {

'id': '642d8848f291652133df8d38',

'tags': [],

'label': 'cat',

'confidence': None,

'logits': None,

}>,

'scene_id': None,

'quality': None,

'more_tags': None,

'info': None,

'also_tags': None,

'predictions': None,

}>

You can also declare nested fields on existing embedded documents using dot notation:

# Declare a new attribute on a `Classification` field

dataset.add_sample_field("predictions.breed", fo.StringField)

Note

See this section for more options for dynamically expanding the schema of nested lists and embedded documents.

You can use get_field() to

retrieve a Field instance by its name or embedded.field.name. And, if the

field contains an embedded document, you can call

get_field_schema()

to recursively inspect its nested fields:

field = dataset.get_field("predictions")

print(field.document_type)

# <class 'fiftyone.core.labels.Classification'>

print(set(field.get_field_schema().keys()))

# {'logits', 'confidence', 'breed', 'tags', 'label', 'id'}

# Directly retrieve a nested field

field = dataset.get_field("predictions.breed")

print(type(field))

# <class 'fiftyone.core.fields.StringField'>

If your dataset contains a ListField with no value type declared, you can add

the type later by appending [] to the field path:

field = dataset.get_field("more_tags")

print(field.field) # None

# Declare the subfield types of an existing untyped list field

dataset.add_sample_field("more_tags[]", fo.StringField)

field = dataset.get_field("more_tags")

print(field.field) # StringField

# List fields can also contain embedded documents

dataset.add_sample_field(

"info[]",

fo.EmbeddedDocumentField,

embedded_doc_type=fo.DynamicEmbeddedDocument,

)

field = dataset.get_field("info")

print(field.field) # EmbeddedDocumentField

print(field.field.document_type) # DynamicEmbeddedDocument

Note

Declaring the value type of list fields is required if you want to filter by the list’s values in the App.

Editing sample fields¶

You can make any edits you wish to the fields of an existing Sample:

sample = fo.Sample(

filepath="/path/to/image.jpg",

ground_truth=fo.Detections(

detections=[\

fo.Detection(label="CAT", bounding_box=[0.1, 0.1, 0.4, 0.4]),\

fo.Detection(label="dog", bounding_box=[0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.4]),\

]

)

)

detections = sample.ground_truth.detections

# Edit an existing detection

detections[0].label = "cat"

# Add a new detection

new_detection = fo.Detection(label="animals", bounding_box=[0, 0, 1, 1])

detections.append(new_detection)

print(sample)

sample.save() # if the sample is in a dataset

Note

You must call sample.save() in

order to persist changes to the database when editing samples that are in

datasets.

A common workflow is to iterate over a dataset or view and edit each sample:

for sample in dataset:

sample["new_field"] = ...

sample.save()

The iter_samples() method

is an equivalent way to iterate over a dataset that provides a

progress=True option that prints a progress bar tracking the status of the

iteration:

# Prints a progress bar tracking the status of the iteration

for sample in dataset.iter_samples(progress=True):

sample["new_field"] = ...

sample.save()

The iter_samples() method

also provides an autosave=True option that causes all changes to samples

emitted by the iterator to be automatically saved using efficient batch

updates:

# Automatically saves sample edits in efficient batches

for sample in dataset.iter_samples(autosave=True):

sample["new_field"] = ...

Using autosave=True can significantly improve performance when editing

large datasets. See this section for more information

on batch update patterns.

Removing fields from a sample ¶¶

A field can be deleted from a Sample using del:

del sample["integer_field"]

If the Sample is not yet in a dataset, deleting a field will remove it from

the sample. If the Sample is in a dataset, the field’s value will be None.

Fields can also be deleted at the Dataset level, in which case they are

removed from every Sample in the dataset:

dataset.delete_sample_field("integer_field")

sample.integer_field

# AttributeError: Sample has no field 'integer_field'

Storing field metadata ¶¶

You can store metadata such as descriptions and other info on the fields of your dataset.

One approach is to manually declare the field with

add_sample_field()

with the appropriate metadata provided:

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

dataset.add_sample_field(

"int_field", fo.IntField, description="An integer field"

)

field = dataset.get_field("int_field")

print(field.description) # An integer field

You can also use

get_field() to

retrieve a field and update it’s metadata at any time:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart")

dataset.add_dynamic_sample_fields()

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth")

field.description = "Ground truth annotations"

field.info = {"url": "https://fiftyone.ai"}

field.save() # must save after edits

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth.detections.area")

field.description = "Area of the box, in pixels^2"

field.info = {"url": "https://fiftyone.ai"}

field.save() # must save after edits

dataset.reload()

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth")

print(field.description) # Ground truth annotations

print(field.info) # {'url': 'https://fiftyone.ai'}

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth.detections.area")

print(field.description) # Area of the box, in pixels^2

print(field.info) # {'url': 'https://fiftyone.ai'}

Note

You must call

field.save() after updating

a fields’s description

and info attributes in-place to

save the changes to the database.

Note

Did you know? You can view field metadata directly in the App by hovering over fields or attributes in the sidebar!

Read-only fields ¶¶

Certain default sample fields like created_at

and last_modified_at are read-only and thus cannot be manually edited:

from datetime import datetime

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.jpg")

dataset = fo.Dataset()

dataset.add_sample(sample)

sample.created_at = datetime.utcnow()

# ValueError: Cannot edit read-only field 'created_at'

sample.last_modified_at = datetime.utcnow()

# ValueError: Cannot edit read-only field 'last_modified_at'

You can also manually mark additional fields or embedded fields as read-only at any time:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart")

# Declare a new read-only field

dataset.add_sample_field("uuid", fo.StringField, read_only=True)

# Mark 'filepath' as read-only

field = dataset.get_field("filepath")

field.read_only = True

field.save() # must save after edits

# Mark a nested field as read-only

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth.detections.label")

field.read_only = True

field.save() # must save after edits

sample = dataset.first()

sample.filepath = "no.jpg"

# ValueError: Cannot edit read-only field 'filepath'

sample.ground_truth.detections[0].label = "no"

sample.save()

# ValueError: Cannot edit read-only field 'ground_truth.detections.label'

Note

You must call

field.save() after updating

a fields’s read_only

attributes in-place to save the changes to the database.

Note that read-only fields do not interfere with the ability to add/delete samples from datasets:

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.jpg", uuid="1234")

dataset.add_sample(sample)

dataset.delete_samples(sample)

Any fields that you’ve manually marked as read-only may be reverted to editable at any time:

sample = dataset.first()

# Revert 'filepath' to editable

field = dataset.get_field("filepath")

field.read_only = False

field.save() # must save after edits

# Revert nested field to editable

field = dataset.get_field("ground_truth.detections.label")

field.read_only = False

field.save() # must save after edits

sample.filepath = "yes.jpg"

sample.ground_truth.detections[0].label = "yes"

sample.save()

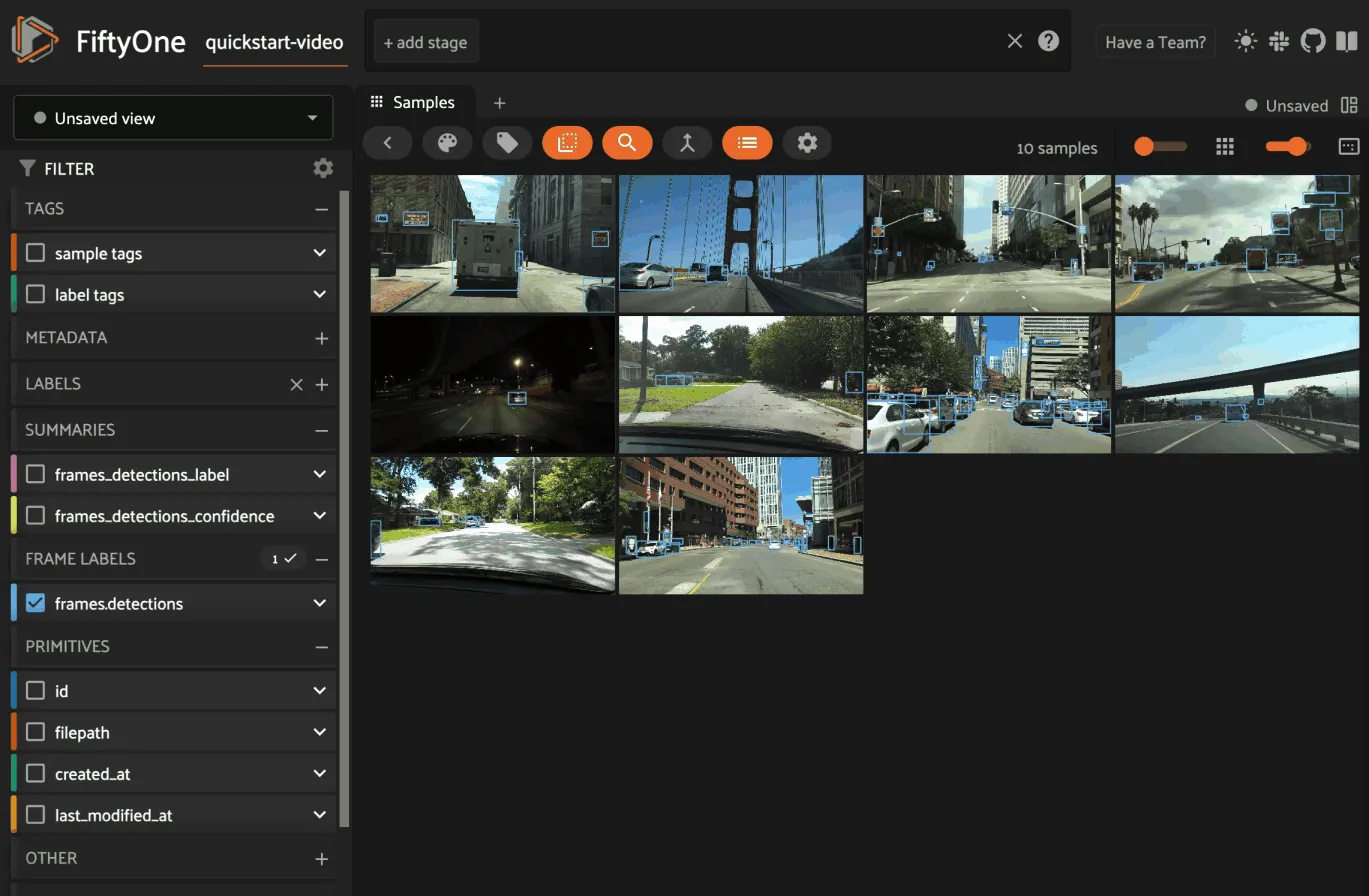

Summary fields ¶¶

Summary fields allow you to efficiently perform queries on large datasets where directly querying the underlying field is prohibitively slow due to the number of objects/frames in the field.

For example, suppose you’re working on a

video dataset with frame-level objects, and you’re

interested in finding videos that contain specific classes of interest, eg

person, in at least one frame:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

from fiftyone import ViewField as F

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart-video")

dataset.set_field("frames.detections.detections.confidence", F.rand()).save()

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

One approach is to directly query the frame-level field ( frames.detections

in this case) in the App’s sidebar. However, when the dataset is large, such

queries are inefficient, as they cannot unlock

query performance and thus require

full collection scans over all frames to retrieve the relevant samples.

A more efficient approach is to first use

create_summary_field()

to summarize the relevant input field path(s):

# Generate a summary field for object labels

field_name = dataset.create_summary_field("frames.detections.detections.label")

# The name of the summary field that was created

print(field_name)

# 'frames_detections_label'

# Generate a summary field for [min, max] confidences

dataset.create_summary_field("frames.detections.detections.confidence")

Summary fields can be generated for sample-level and frame-level fields, and the input fields can be either categorical or numeric:

As the above examples illustrate, summary fields allow you to encode various types of information at the sample-level that you can directly query to find samples that contain specific values.

Moreover, summary fields are indexed by default and the App can natively leverage these indexes to provide performant filtering:

Note

Summary fields are automatically added to a summaries sidebar group in the App for

easy access and organization.

They are also read-only by default, as they are implicitly derived from the contents of their source field and are not intended to be directly modified.

You can use

list_summary_fields()

to list the names of the summary fields on your dataset:

print(dataset.list_summary_fields())

# ['frames_detections_label', 'frames_detections_confidence', ...]

Since a summary field is derived from the contents of another field, it must be

updated whenever there have been modifications to its source field. You can use

check_summary_fields()

to check for summary fields that may need to be updated:

# Newly created summary fields don't needed updating

print(dataset.check_summary_fields())

# []

# Modify the dataset

label_upper = F("label").upper()

dataset.set_field("frames.detections.detections.label", label_upper).save()

# Summary fields now (may) need updating

print(dataset.check_summary_fields())

# ['frames_detections_label', 'frames_detections_confidence', ...]

Note

Note that inclusion in

check_summary_fields()

is only a heuristic, as any sample modifications may not have affected

the summary’s source field.

Use update_summary_field()

to regenerate a summary field based on the current values of its source field:

dataset.update_summary_field("frames_detections_label")

Finally, use

delete_summary_field()

or delete_summary_fields()

to delete existing summary field(s) that you no longer need:

dataset.delete_summary_field("frames_detections_label")

Media type ¶¶

When a Sample is created, its media type is inferred from the filepath to

the source media and available via the media_type attribute of the sample,

which is read-only.

Media type is inferred from the MIME type of the file on disk, as per the table below:

| MIME type/extension | media_type |

Description |

|---|---|---|

image/* |

image |

Image sample |

video/* |

video |

Video sample |

*.fo3d |

3d |

3D sample |

*.pcd |

point-cloud |

Point cloud sample |

| other | - |

Generic sample |

Note

The filepath of a sample can be changed after the sample is created, but

the new filepath must have the same media type. In other words,

media_type is immutable.

Tags ¶¶

All Sample instances have a tags field, which is a string list. By default,

this list is empty, but you can use it to store information like dataset splits

or application-specific issues like low quality images:

dataset = fo.Dataset("tagged_dataset")

dataset.add_samples(

[\

fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image1.png", tags=["train"]),\

fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image2.png", tags=["test", "low_quality"]),\

]

)

print(dataset.distinct("tags"))

# ["test", "low_quality", "train"]

Note

Did you know? You can add, edit, and filter by sample tags directly in the App.

The tags field can be used like a standard Python list:

sample = dataset.first()

sample.tags.append("new_tag")

sample.save()

Note

You must call sample.save() in

order to persist changes to the database when editing samples that are in

datasets.

Datasets and views provide helpful methods such as

count_sample_tags(),

tag_samples(),

untag_samples(),

and

match_tags()

that you can use to perform batch queries and edits to sample tags:

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart").clone()

print(dataset.count_sample_tags()) # {'validation': 200}

# Tag samples in a view

test_view = dataset.limit(100)

test_view.untag_samples("validation")

test_view.tag_samples("test")

print(dataset.count_sample_tags()) # {'validation': 100, 'test': 100}

# Create a view containing samples with a specific tag

validation_view = dataset.match_tags("validation")

print(len(validation_view)) # 100

Metadata ¶¶

All Sample instances have a metadata field, which can optionally be

populated with a Metadata instance that stores data type-specific metadata

about the raw data in the sample. The FiftyOne App and

the FiftyOne Brain will use this provided metadata in

some workflows when it is available.

Dates and datetimes ¶¶

You can store date information in FiftyOne datasets by populating fields with

date or datetime values:

from datetime import date, datetime

import fiftyone as fo

dataset = fo.Dataset()

dataset.add_samples(

[\

fo.Sample(\

filepath="image1.png",\

acquisition_time=datetime(2021, 8, 24, 21, 18, 7),\

acquisition_date=date(2021, 8, 24),\

),\

fo.Sample(\

filepath="image2.png",\

acquisition_time=datetime.utcnow(),\

acquisition_date=date.today(),\

),\

]

)

print(dataset)

print(dataset.head())

Note

Did you know? You can create dataset views with date-based queries!

Internally, FiftyOne stores all dates as UTC timestamps, but you can provide

any valid datetime object when setting a DateTimeField of a sample,

including timezone-aware datetimes, which are internally converted to UTC

format for safekeeping.

# A datetime in your local timezone

now = datetime.utcnow().astimezone()

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="image.png", acquisition_time=now)

dataset = fo.Dataset()

dataset.add_sample(sample)

# Samples are singletons, so we reload so `sample` will contain values as

# loaded from the database

dataset.reload()

sample.acquisition_time.tzinfo # None

By default, when you access a datetime field of a sample in a dataset, it is

retrieved as a naive datetime instance expressed in UTC format.

However, if you prefer, you can

configure FiftyOne to load datetime fields as

timezone-aware datetime instances in a timezone of your choice.

Warning

FiftyOne assumes that all datetime instances with no explicit timezone

are stored in UTC format.

Therefore, never use datetime.datetime.now() when populating a datetime

field of a FiftyOne dataset! Instead, use datetime.datetime.utcnow().

Labels ¶¶

The Label class hierarchy is used to store semantic information about ground

truth or predicted labels in a sample.

Although such information can be stored in custom sample fields

(e.g, in a DictField), it is recommended that you store label information in

Label instances so that the FiftyOne App and the

FiftyOne Brain can visualize and compute on your

labels.

Note

All Label instances are dynamic! You can add custom fields to your

labels to store custom information:

# Provide some default fields

label = fo.Classification(label="cat", confidence=0.98)

# Add custom fields

label["int"] = 5

label["float"] = 51.0

label["list"] = [1, 2, 3]

label["bool"] = True

label["dict"] = {"key": ["list", "of", "values"]}

You can also declare dynamic attributes on your dataset’s schema, which allows you to enforce type constraints, filter by these custom attributes in the App, and more.

FiftyOne provides a dedicated Label subclass for many common tasks. The

subsections below describe them.

Regression ¶¶

The Regression class represents a numeric regression value for an image. The

value itself is stored in the

value attribute of the

Regression object. This may be a ground truth value or a model prediction.

The optional

confidence attribute can

be used to store a score associated with the model prediction and can be

visualized in the App or used, for example, when

evaluating regressions.

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["ground_truth"] = fo.Regression(value=51.0)

sample["prediction"] = fo.Classification(value=42.0, confidence=0.9)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'ground_truth': <Regression: {

'id': '616c4bef36297ec40a26d112',

'tags': [],

'value': 51.0,

'confidence': None,

}>,

'prediction': <Classification: {

'id': '616c4bef36297ec40a26d113',

'tags': [],

'label': None,

'confidence': 0.9,

'logits': None,

'value': 42.0,

}>,

}>

Classification ¶¶

The Classification class represents a classification label for an image. The

label itself is stored in the

label attribute of the

Classification object. This may be a ground truth label or a model

prediction.

The optional

confidence and

logits attributes may be

used to store metadata about the model prediction. These additional fields can

be visualized in the App or used by Brain methods, e.g., when

computing label mistakes.

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["ground_truth"] = fo.Classification(label="sunny")

sample["prediction"] = fo.Classification(label="sunny", confidence=0.9)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'ground_truth': <Classification: {

'id': '5f8708db2018186b6ef66821',

'label': 'sunny',

'confidence': None,

'logits': None,

}>,

'prediction': <Classification: {

'id': '5f8708db2018186b6ef66822',

'label': 'sunny',

'confidence': 0.9,

'logits': None,

}>,

}>

Note

Did you know? You can store class lists for your models on your datasets.

Multilabel classification ¶¶

The Classifications class represents a list of classification labels for an

image. The typical use case is to represent multilabel annotations/predictions

for an image, where multiple labels from a model may apply to a given image.

The labels are stored in a

classifications

attribute of the object, which contains a list of Classification instances.

Metadata about individual labels can be stored in the Classification

instances as usual; additionally, you can optionally store logits for the

overarching model (if applicable) in the

logits attribute of the

Classifications object.

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["ground_truth"] = fo.Classifications(

classifications=[\

fo.Classification(label="animal"),\

fo.Classification(label="cat"),\

fo.Classification(label="tabby"),\

]

)

sample["prediction"] = fo.Classifications(

classifications=[\

fo.Classification(label="animal", confidence=0.99),\

fo.Classification(label="cat", confidence=0.98),\

fo.Classification(label="tabby", confidence=0.72),\

]

)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'ground_truth': <Classifications: {

'classifications': [\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66823',\

'label': 'animal',\

'confidence': None,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66824',\

'label': 'cat',\

'confidence': None,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66825',\

'label': 'tabby',\

'confidence': None,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

],

'logits': None,

}>,

'prediction': <Classifications: {

'classifications': [\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66826',\

'label': 'animal',\

'confidence': 0.99,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66827',\

'label': 'cat',\

'confidence': 0.98,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

<Classification: {\

'id': '5f8708f62018186b6ef66828',\

'label': 'tabby',\

'confidence': 0.72,\

'logits': None,\

}>,\

],

'logits': None,

}>,

}>

Note

Did you know? You can store class lists for your models on your datasets.

Object detection¶

The Detections class represents a list of object detections in an image. The

detections are stored in the

detections attribute of

the Detections object.

Each individual object detection is represented by a Detection object. The

string label of the object should be stored in the

label attribute, and the

bounding box for the object should be stored in the

bounding_box attribute.

Note

FiftyOne stores box coordinates as floats in [0, 1] relative to the

dimensions of the image. Bounding boxes are represented by a length-4 list

in the format:

[<top-left-x>, <top-left-y>, <width>, <height>]

Note

Did you know? FiftyOne also supports 3D detections!

In the case of model predictions, an optional confidence score for each

detection can be stored in the

confidence attribute.

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["ground_truth"] = fo.Detections(

detections=[fo.Detection(label="cat", bounding_box=[0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3])]

)

sample["prediction"] = fo.Detections(

detections=[\

fo.Detection(\

label="cat",\

bounding_box=[0.480, 0.513, 0.397, 0.288],\

confidence=0.96,\

),\

]

)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'ground_truth': <Detections: {

'detections': [\

<Detection: {\

'id': '5f8709172018186b6ef66829',\

'attributes': {},\

'label': 'cat',\

'bounding_box': [0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3],\

'mask': None,\

'confidence': None,\

'index': None,\

}>,\

],

}>,

'prediction': <Detections: {

'detections': [\

<Detection: {\

'id': '5f8709172018186b6ef6682a',\

'attributes': {},\

'label': 'cat',\

'bounding_box': [0.48, 0.513, 0.397, 0.288],\

'mask': None,\

'confidence': 0.96,\

'index': None,\

}>,\

],

}>,

}>

Note

Did you know? You can store class lists for your models on your datasets.

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your detections

by dynamically adding new fields to each Detection instance:

import fiftyone as fo

detection = fo.Detection(

label="cat",

bounding_box=[0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3],

age=51, # custom attribute

mood="salty", # custom attribute

)

print(detection)

<Detection: {

'id': '60f7458c467d81f41c200551',

'attributes': {},

'tags': [],

'label': 'cat',

'bounding_box': [0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3],

'mask': None,

'confidence': None,

'index': None,

'age': 51,

'mood': 'salty',

}>

Note

Did you know? You can view custom attributes in the App tooltip by hovering over the objects.

Instance segmentations ¶¶

Object detections stored in Detections may also have instance segmentation

masks.

These masks can be stored in one of two ways: either directly in the database

via the mask attribute, or on

disk referenced by the

mask_path attribute.

Masks stored directly in the database must be 2D numpy arrays

containing either booleans or 0/1 integers that encode the extent of the

instance mask within the

bounding_box of the

object.

For masks stored on disk, the

mask_path attribute should

contain the file path to the mask image. We recommend storing masks as

single-channel PNG images, where a pixel value of 0 indicates the

background (rendered as transparent in the App), and any other

value indicates the object.

Masks can be of any size; they are stretched as necessary to fill the object’s bounding box when visualizing in the App.

import numpy as np

from PIL import Image

import fiftyone as fo

# Example instance mask

mask = ((np.random.randn(32, 32) > 0) * 255).astype(np.uint8)

mask_path = "/path/to/mask.png"

Image.fromarray(mask).save(mask_path)

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["prediction"] = fo.Detections(

detections=[\

fo.Detection(\

label="cat",\

bounding_box=[0.480, 0.513, 0.397, 0.288],\

mask_path=mask_path,\

confidence=0.96,\

),\

]

)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'prediction': <Detections: {

'detections': [\

<Detection: {\

'id': '5f8709282018186b6ef6682b',\

'attributes': {},\

'tags': [],\

'label': 'cat',\

'bounding_box': [0.48, 0.513, 0.397, 0.288],\

'mask': None,\

'mask_path': '/path/to/mask.png',\

'confidence': 0.96,\

'index': None,\

}>,\

],

}>,

}>

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your instance

segmentations by dynamically adding new fields to each Detection instance:

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

detection = fo.Detection(

label="cat",

bounding_box=[0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3],

mask_path="/path/to/mask.png",

age=51, # custom attribute

mood="salty", # custom attribute

)

print(detection)

<Detection: {

'id': '60f74568467d81f41c200550',

'attributes': {},

'tags': [],

'label': 'cat',

'bounding_box': [0.5, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3],

'mask_path': '/path/to/mask.png',

'confidence': None,

'index': None,

'age': 51,

'mood': 'salty',

}>

Note

Did you know? You can view custom attributes in the App tooltip by hovering over the objects.

Polylines and polygons ¶¶

The Polylines class represents a list of

polylines or

polygons in an image. The polylines

are stored in the

polylines attribute of the

Polylines object.

Each individual polyline is represented by a Polyline object, which

represents a set of one or more semantically related shapes in an image. The

points attribute contains a

list of lists of (x, y) coordinates defining the vertices of each shape

in the polyline. If the polyline represents a closed curve, you can set the

closed attribute to True to

indicate that a line segment should be drawn from the last vertex to the first

vertex of each shape in the polyline. If the shapes should be filled when

rendering them, you can set the

filled attribute to True.

Polylines can also have string labels, which are stored in their

label attribute.

Note

FiftyOne stores vertex coordinates as floats in [0, 1] relative to the

dimensions of the image.

Note

Did you know? FiftyOne also supports 3D polylines!

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

# A simple polyline

polyline1 = fo.Polyline(

points=[[(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3)]],

closed=False,

filled=False,

)

# A closed, filled polygon with a label

polyline2 = fo.Polyline(

label="triangle",

points=[[(0.1, 0.1), (0.3, 0.1), (0.3, 0.3)]],

closed=True,

filled=True,

)

sample["polylines"] = fo.Polylines(polylines=[polyline1, polyline2])

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'polylines': <Polylines: {

'polylines': [\

<Polyline: {\

'id': '5f87094e2018186b6ef6682e',\

'attributes': {},\

'label': None,\

'points': [[(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3)]],\

'index': None,\

'closed': False,\

'filled': False,\

}>,\

<Polyline: {\

'id': '5f87094e2018186b6ef6682f',\

'attributes': {},\

'label': 'triangle',\

'points': [[(0.1, 0.1), (0.3, 0.1), (0.3, 0.3)]],\

'index': None,\

'closed': True,\

'filled': True,\

}>,\

],

}>,

}>

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your polylines by

dynamically adding new fields to each Polyline instance:

import fiftyone as fo

polyline = fo.Polyline(

label="triangle",

points=[[(0.1, 0.1), (0.3, 0.1), (0.3, 0.3)]],

closed=True,

filled=True,

kind="right", # custom attribute

)

print(polyline)

<Polyline: {

'id': '60f746b4467d81f41c200555',

'attributes': {},

'tags': [],

'label': 'triangle',

'points': [[(0.1, 0.1), (0.3, 0.1), (0.3, 0.3)]],

'confidence': None,

'index': None,

'closed': True,

'filled': True,

'kind': 'right',

}>

Note

Did you know? You can view custom attributes in the App tooltip by hovering over the objects.

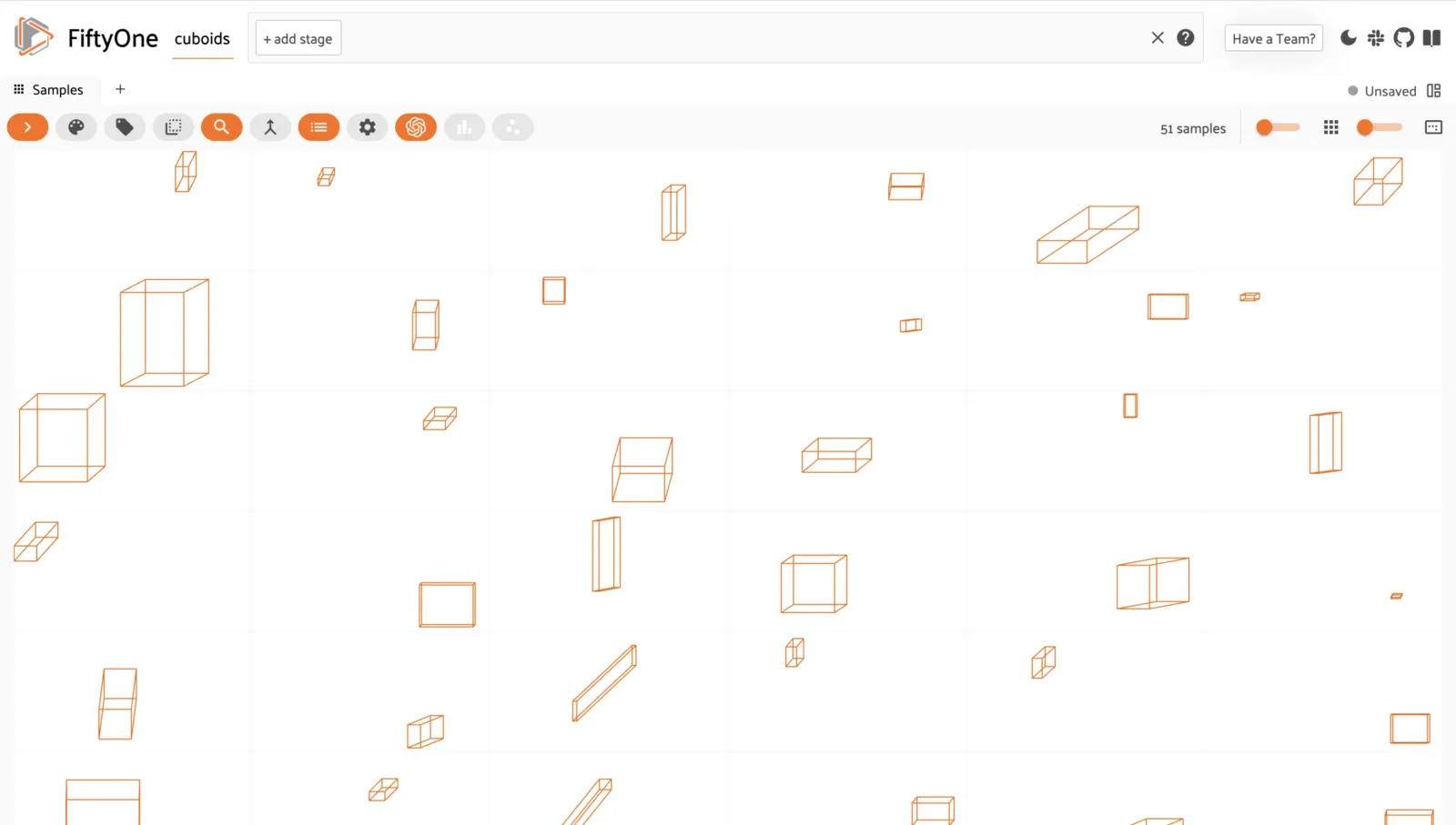

Cuboids ¶¶

You can store and visualize cuboids in FiftyOne using the

Polyline.from_cuboid()

method.

The method accepts a list of 8 (x, y) points describing the vertices of the

cuboid in the format depicted below:

7--------6

/| /|

/ | / |

3--------2 |

| 4-----|--5

| / | /

|/ |/

0--------1

Note

FiftyOne stores vertex coordinates as floats in [0, 1] relative to the

dimensions of the image.

import cv2

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

def random_cuboid(frame_size):

width, height = frame_size

x0, y0 = np.array([width, height]) * ([0, 0.2] + 0.8 * np.random.rand(2))

dx, dy = (min(0.8 * width - x0, y0 - 0.2 * height)) * np.random.rand(2)

x1, y1 = x0 + dx, y0 - dy

w, h = (min(width - x1, y1)) * np.random.rand(2)

front = [(x0, y0), (x0 + w, y0), (x0 + w, y0 - h), (x0, y0 - h)]

back = [(x1, y1), (x1 + w, y1), (x1 + w, y1 - h), (x1, y1 - h)]

vertices = front + back

return fo.Polyline.from_cuboid(

vertices, frame_size=frame_size, label="cuboid"

)

frame_size = (256, 128)

filepath = "/tmp/image.png"

size = (frame_size[1], frame_size[0], 3)

cv2.imwrite(filepath, np.full(size, 255, dtype=np.uint8))

dataset = fo.Dataset("cuboids")

dataset.add_samples(

[\

fo.Sample(filepath=filepath, cuboid=random_cuboid(frame_size))\

for _ in range(51)]

)

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your cuboids by

dynamically adding new fields to each Polyline instance:

polyline = fo.Polyline.from_cuboid(

vertics, frame_size=frame_size,

label="vehicle",

filled=True,

type="sedan", # custom attribute

)

Note

Did you know? You can view custom attributes in the App tooltip by hovering over the objects.

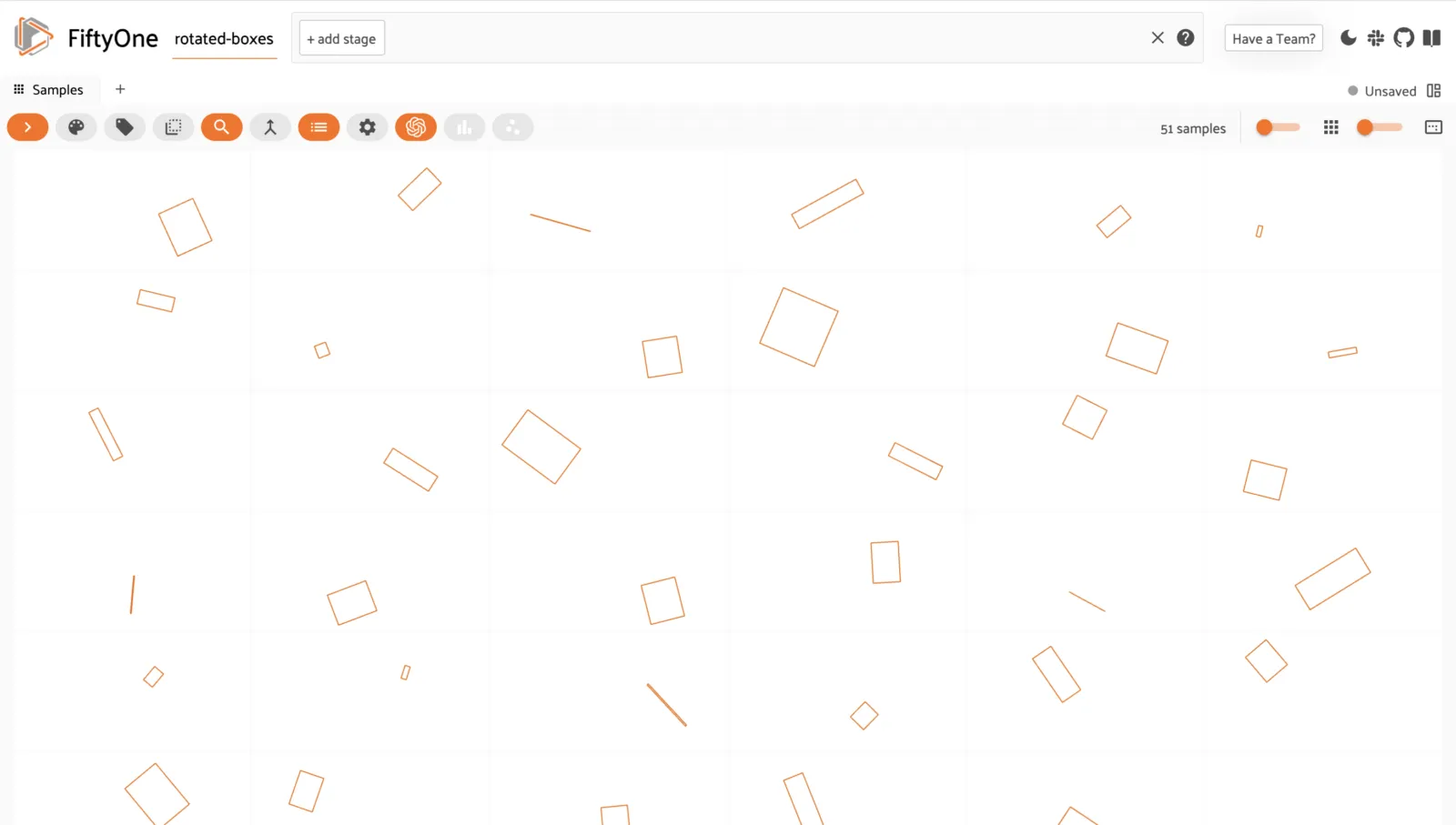

Rotated bounding boxes ¶¶

You can store and visualize rotated bounding boxes in FiftyOne using the

Polyline.from_rotated_box()

method, which accepts rotated boxes described by their center coordinates,

width/height, and counter-clockwise rotation, in radians.

Note

FiftyOne stores vertex coordinates as floats in [0, 1] relative to the

dimensions of the image.

import cv2

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

def random_rotated_box(frame_size):

width, height = frame_size

xc, yc = np.array([width, height]) * (0.2 + 0.6 * np.random.rand(2))

w, h = 1.5 * (min(xc, yc, width - xc, height - yc)) * np.random.rand(2)

theta = 2 * np.pi * np.random.rand()

return fo.Polyline.from_rotated_box(

xc, yc, w, h, theta, frame_size=frame_size, label="box"

)

frame_size = (256, 128)

filepath = "/tmp/image.png"

size = (frame_size[1], frame_size[0], 3)

cv2.imwrite(filepath, np.full(size, 255, dtype=np.uint8))

dataset = fo.Dataset("rotated-boxes")

dataset.add_samples(

[\

fo.Sample(filepath=filepath, box=random_rotated_box(frame_size))\

for _ in range(51)\

]

)

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your rotated

bounding boxes by dynamically adding new fields to each Polyline instance:

polyline = fo.Polyline.from_rotated_box(

xc, yc, width, height, theta, frame_size=frame_size,

label="cat",

mood="surly", # custom attribute

)

Note

Did you know? You can view custom attributes in the App tooltip by hovering over the objects.

Keypoints ¶¶

The Keypoints class represents a collection of keypoint groups in an image.

The keypoint groups are stored in the

keypoints attribute of the

Keypoints object. Each element of this list is a Keypoint object whose

points attribute contains a

list of (x, y) coordinates defining a group of semantically related

keypoints in the image.

For example, if you are working with a person model that outputs 18 keypoints

( left eye, right eye, nose, etc.) per person, then each Keypoint

instance would represent one person, and a Keypoints instance would represent

the list of people in the image.

Note

FiftyOne stores keypoint coordinates as floats in [0, 1] relative to the

dimensions of the image.

Each Keypoint object can have a string label, which is stored in its

label attribute, and it can

optionally have a list of per-point confidences in [0, 1] in its

confidence attribute:

import fiftyone as fo

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["keypoints"] = fo.Keypoints(

keypoints=[\

fo.Keypoint(\

label="square",\

points=[(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.7), (0.3, 0.7)],\

confidence=[0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9],\

)\

]

)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'keypoints': <Keypoints: {

'keypoints': [\

<Keypoint: {\

'id': '5f8709702018186b6ef66831',\

'attributes': {},\

'label': 'square',\

'points': [(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.7), (0.3, 0.7)],\

'confidence': [0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9],\

'index': None,\

}>,\

],

}>,

}>

Like all Label types, you can also add custom attributes to your keypoints by

dynamically adding new fields to each Keypoint instance. As a special case,

if you add a custom list attribute to a Keypoint instance whose length

matches the number of points, these values will be interpreted as per-point

attributes and rendered as such in the App:

import fiftyone as fo

keypoint = fo.Keypoint(

label="rectangle",

kind="square", # custom object attribute

points=[(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.7), (0.3, 0.7)],

confidence=[0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9],

occluded=[False, False, True, False], # custom per-point attributes

)

print(keypoint)

<Keypoint: {

'id': '60f74723467d81f41c200556',

'attributes': {},

'tags': [],

'label': 'rectangle',

'points': [(0.3, 0.3), (0.7, 0.3), (0.7, 0.7), (0.3, 0.7)],

'confidence': [0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9],

'index': None,

'kind': 'square',

'occluded': [False, False, True, False],

}>

If your keypoints have semantic meanings, you can store keypoint skeletons on your dataset to encode the meanings.

If you are working with keypoint skeletons and a particular point is missing or not visible for an instance, use nan values for its coordinates:

keypoint = fo.Keypoint(

label="rectangle",

points=[\

(0.3, 0.3),\

(float("nan"), float("nan")), # use nan to encode missing points\

(0.7, 0.7),\

(0.3, 0.7),\

],

)

Note

Did you know? When you view datasets with keypoint skeletons in the App, label strings and edges will be drawn when you visualize the keypoint fields.

Semantic segmentation ¶¶

The Segmentation class represents a semantic segmentation mask for an image

with integer values encoding the semantic labels for each pixel in the image.

The mask can either be stored on disk and referenced via the

mask_path attribute or

stored directly in the database via the

mask attribute.

Note

It is recommended to store segmentations on disk and reference them via the

mask_path attribute,

for efficiency.

Note that mask_path

must contain the absolute path to the mask on disk in order to use the

dataset from different current working directories in the future.

Segmentation masks can be stored in either of these formats:

-

2D 8-bit or 16-bit images or numpy arrays

-

3D 8-bit RGB images or numpy arrays

Segmentation masks can have any size; they are stretched as necessary to fit the image’s extent when visualizing in the App.

import cv2

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

# Example segmentation mask

mask_path = "/tmp/segmentation.png"

mask = np.random.randint(10, size=(128, 128), dtype=np.uint8)

cv2.imwrite(mask_path, mask)

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["segmentation1"] = fo.Segmentation(mask_path=mask_path)

sample["segmentation2"] = fo.Segmentation(mask=mask)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'segmentation1': <Segmentation: {

'id': '6371d72425de9907b93b2a6b',

'tags': [],

'mask': None,

'mask_path': '/tmp/segmentation.png',

}>,

'segmentation2': <Segmentation: {

'id': '6371d72425de9907b93b2a6c',

'tags': [],

'mask': array([[8, 5, 5, ..., 9, 8, 5],\

[0, 7, 8, ..., 3, 4, 4],\

[5, 0, 2, ..., 0, 3, 4],\

...,\

[4, 4, 4, ..., 3, 6, 6],\

[0, 9, 8, ..., 8, 0, 8],\

[0, 6, 8, ..., 2, 9, 1]], dtype=uint8),

'mask_path': None,

}>,

}>

When you load datasets with Segmentation fields containing 2D masks in the

App, each pixel value is rendered as a different color (if possible) from the

App’s color pool. When you view RGB segmentation masks in the App, the mask

colors are always used.

Note

Did you know? You can store semantic labels for your segmentation fields on your dataset. Then, when you view the dataset in the App, label strings will appear in the App’s tooltip when you hover over pixels.

Note

The pixel value 0 and RGB value #000000 are reserved “background”

classes that are always rendered as invisible in the App.

If mask targets are provided, all observed values not present in the targets are also rendered as invisible in the App.

Heatmaps ¶¶

The Heatmap class represents a continuous-valued heatmap for an image.

The map can either be stored on disk and referenced via the

map_path attribute or stored

directly in the database via the map

attribute. When using the

map_path attribute, heatmaps

may be 8-bit or 16-bit grayscale images. When using the

map attribute, heatmaps should be 2D

numpy arrays. By default, the map values are assumed to be in [0, 1] for

floating point arrays and [0, 255] for integer-valued arrays, but you can

specify a custom [min, max] range for a map by setting its optional

range attribute.

Heatmaps can have any size; they are stretched as necessary to fit the image’s extent when visualizing in the App.

Note

It is recommended to store heatmaps on disk and reference them via the

map_path attribute, for

efficiency.

Note that map_path

must contain the absolute path to the map on disk in order to use the

dataset from different current working directories in the future.

import cv2

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

# Example heatmap

map_path = "/tmp/heatmap.png"

map = np.random.randint(256, size=(128, 128), dtype=np.uint8)

cv2.imwrite(map_path, map)

sample = fo.Sample(filepath="/path/to/image.png")

sample["heatmap1"] = fo.Heatmap(map_path=map_path)

sample["heatmap2"] = fo.Heatmap(map=map)

print(sample)

<Sample: {

'id': None,

'media_type': 'image',

'filepath': '/path/to/image.png',

'tags': [],

'metadata': None,

'created_at': None,

'last_modified_at': None,

'heatmap1': <Heatmap: {

'id': '6371d9e425de9907b93b2a6f',

'tags': [],

'map': None,

'map_path': '/tmp/heatmap.png',

'range': None,

}>,

'heatmap2': <Heatmap: {

'id': '6371d9e425de9907b93b2a70',

'tags': [],

'map': array([[179, 249, 119, ..., 94, 213, 68],\

[190, 202, 209, ..., 162, 16, 39],\

[252, 251, 181, ..., 221, 118, 231],\

...,\

[ 12, 91, 201, ..., 14, 95, 88],\

[164, 118, 171, ..., 21, 170, 5],\

[232, 156, 218, ..., 224, 97, 65]], dtype=uint8),

'map_path': None,

'range': None,

}>,

}>

When visualizing heatmaps in the App, when the App is

in color-by-field mode, heatmaps are rendered in their field’s color with

opacity proportional to the magnitude of the heatmap’s values. For example, for

a heatmap whose range is

[-10, 10], pixels with the value +9 will be rendered with 90% opacity, and

pixels with the value -3 will be rendered with 30% opacity.

When the App is in color-by-value mode, heatmaps are rendered using the

colormap defined by the colorscale of your

App config, which can be:

-

The string name of any colorscale recognized by Plotly

-

A manually-defined colorscale like the following:

[\

[0.000, "rgb(165,0,38)"],\

[0.111, "rgb(215,48,39)"],\

[0.222, "rgb(244,109,67)"],\

[0.333, "rgb(253,174,97)"],\

[0.444, "rgb(254,224,144)"],\

[0.555, "rgb(224,243,248)"],\

[0.666, "rgb(171,217,233)"],\

[0.777, "rgb(116,173,209)"],\

[0.888, "rgb(69,117,180)"],\

[1.000, "rgb(49,54,149)"],\

]

The example code below demonstrates the possibilities that heatmaps provide by overlaying random gaussian kernels with positive or negative sign on an image dataset and configuring the App’s colorscale in various ways on-the-fly:

import os

import numpy as np

import fiftyone as fo

import fiftyone.zoo as foz

def random_kernel(metadata):

h = metadata.height // 2

w = metadata.width // 2

sign = np.sign(np.random.randn())

x, y = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(-1, 1, w), np.linspace(-1, 1, h))

x0, y0 = np.random.random(2) - 0.5

kernel = sign * np.exp(-np.sqrt((x - x0) ** 2 + (y - y0) ** 2))

return fo.Heatmap(map=kernel, range=[-1, 1])

dataset = foz.load_zoo_dataset("quickstart").select_fields().clone()

dataset.compute_metadata()

for sample in dataset:

heatmap = random_kernel(sample.metadata)

# Convert to on-disk

map_path = os.path.join("/tmp/heatmaps", os.path.basename(sample.filepath))

heatmap.export_map(map_path, update=True)

sample["heatmap"] = heatmap

sample.save()

session = fo.launch_app(dataset)

# Select `Settings -> Color by value` in the App

# Heatmaps will now be rendered using your default colorscale (printed below)

print(session.config.colorscale)

# Switch to a different named colorscale